Download a signed version

Quick guide

Contents

Introduction

We, the Governments of Australia and Singapore (the "Participants"), have together reached the following mutual understandings and jointly developed this Cross-Border Electricity Trade (CBET) Framework (the "Framework"):

- Our Trade Ministers signed the Singapore-Australia Green Economy Agreement (SAGEA) in October 2022 during the 7th Singapore-Australia Leaders' Meeting. The SAGEA is the first of its kind for both countries to promote trade and investment in the energy transition. It seeks to foster common rules and standards that promote trade and investment in green goods, services and technologies; develop interoperable policy frameworks to support the growth of new green growth sectors and capabilities; and catalyse technology development and cooperative projects in the emerging green economy.

- A key initiative under the SAGEA is the development of the architecture for CBET.

- In this context, we jointly developed "Ten Principles to Guide the Development of CBET" to deepen energy connectivity and support CBET ("the Ten Principles"). This was announced at the 9th Singapore-Australia Annual Leaders' Meeting in Melbourne, Australia on 5 March 2024, by Singapore's then-Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong and Australia's Prime Minister Anthony Albanese. The Ten Principles aim to support economic growth, enhance energy security through diverse and resilient clean energy supply chains, and offer clear and predictable guidelines for participants in CBET. They reaffirm our shared commitment to support this new area of trade including the application of relevant trade agreements, law of the sea, safeguarding cross-border electricity infrastructure, developing standards and interoperability, harmonising permitting, establishing governance arrangements and renewable energy certification.

- Building on the spirit of the Ten Principles, Singapore and Australia have jointly developed a CBET Framework, which covers the following topics:

- Section I: Benefits of CBET in Southeast Asia

- Section II: Development and harmonisation of policies and regulations

- Section III: Governance and dispute resolution

- Section IV: RECs and carbon accounting

- Section V: Knowledge-sharing and partnerships

- We also hope that this Framework will serve as a useful point of reference for governments, businesses, investors, and other actors looking to participate in CBET in Southeast Asia, with a view towards enhancing regional energy connectivity and accelerating the realisation of a sustainable, inclusive, and resilient ASEAN Power Grid.

Ten Principles to Guide the Development of CBET

- Deliver economic outcomes that offer tangible benefits across our two countries, where possible, and help facilitate wider participation in CBET with other countries in the region, including by catalysing private sector investments, technological advancements and generating inclusive job opportunities in the clean energy sector.

- Build diverse and resilient clean energy supply chains that are critical to our bilateral energy and economic security, and which could be expanded to the wider region, thereby creating new economic opportunities across the region and supporting acceleration of the global energy transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems.

- Enhance energy security by developing frameworks to safeguard cross-border electricity infrastructure including in transit countries. Where necessary, develop new arrangements to underpin reliable and sustained provision of electricity.

- Promote environmental objectives for the achievement of our respective net-zero targets and international climate change obligations. This includes developing an agreed approach or schemes for renewable energy certification and ensuring that carbon accounting under CBET cooperation is in line with UNFCCC guidelines.

- Uphold our respective commitments under bilateral and multilateral agreements to which both Singapore and Australia are Party, including the Singapore-Australia Free Trade Agreement, WTO Agreements and United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea to enable and facilitate commercial activities that drive CBET.

- Develop and harmonise policies, regulatory and legal frameworks including in relation to required permits for CBET, environmental approvals, liabilities, and safety, to provide certainty to potential investors, businesses and stakeholders.

- Facilitate the compatibility of technical standards and inter-operability of systems that underpin the development, operations and maintenance of CBET and the infrastructure that supports this trade, including by establishing best practices to support regional grid connectivity.

- Establish suitable governance arrangements to provide appropriate oversight, transparency and accountability in CBET, including a mechanism to address any disputes and disagreements.

- Foster mutual understanding and recognition of our respective priorities by sharing knowledge and expertise relevant to the development of CBET.

- Create new partnerships that further enhance CBET, including with regional partners.

Section I: Benefits of Cross-Border Electricity Trade in Southeast Asia

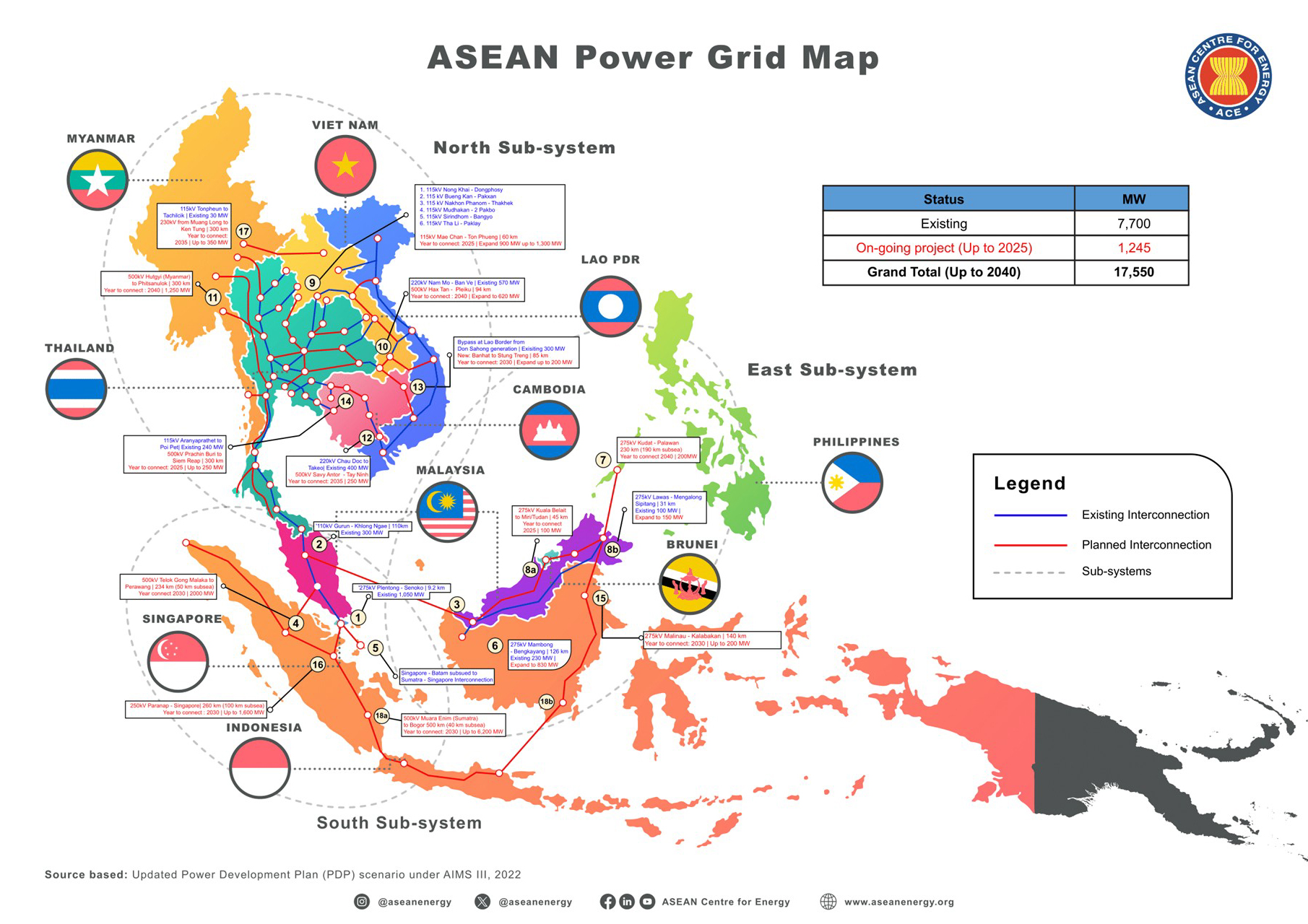

- We affirm the feasibility of CBET in Southeast Asia, as evidenced by ongoing bilateral electricity trade among countries in the region, as well as multilateral pathfinder projects such as the Lao PDR-Thailand-Malaysia-Singapore Power Integration Project. We also note the successful instances of CBET in regions such as Europe and North America, including through long-distance subsea interconnections. There is significant potential to expand interconnector capacity in Southeast Asia, up to approximately 18GW by 2040, to realise the ASEAN Power Grid.

- We also recognise that CBET yields substantial benefits for all countries involved and the region at large.

- It accelerates economic growth; catalyses financing for clean energy by improving the assurance of offtake and consequently the bankability of clean energy projects and associated interconnector infrastructure; promotes technological development; creates high-quality and green jobs for local communities; grants importing countries access to cost-competitive sources of energy; and generates revenue for exporting transit countries from the sale of electrons, as well as for transit countries from wheeling charges for electricity transmitted through their grids.

- It enhances energy access and security, against the backdrop of a projected increase in electricity demand in ASEAN by more than 60 per cent by 2050. The ability to access surplus electricity in other countries and share reserve capacities can mitigate the impact of shocks and enhance system stability; as well as reduce the need for building domestic back-up or storage capacity and lower system costs. The integration of grids with different energy mixes and the diversification of sources of supply further enhances energy security. As the share of renewable energy in the region's energy mix increases, CBET can also help to manage intermittency in renewable energy output.

- It is a critical pathway to decarbonisation in the region, bearing in mind that power generation accounts for approximately 40% of Southeast Asia's current emissions. Crucially, CBET in Southeast Asia enables the region to decarbonise and enhance energy security by harnessing its indigenous wealth of renewable resources, mitigating the region's increasing reliance on imported fossil fuels. This in turn promotes regional resilience and unity in an increasingly fragmented and geopolitically contested world.

- The case study in Annex I demonstrates how Australia integrated several sub-national electricity grids into a single National Energy Market in the 1990s. While this case study occurs within Australia's borders, it still serves to illustrate the potential challenges and benefits in the process of implementing CBET between countries.

This map from the ASEAN Centre for Energy shows the ASEAN Power Grid and its three sub-systems (North, East and South). It highlights existing (blue lines) and planned (red dashed lines) cross-border electricity interconnections among ASEAN member states — Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei Darussalam, Indonesia, and the Philippines. The total interconnected capacity is 17,550 MW, comprising 7,700 MW existing and 9,850 MW in ongoing projects (up to 2025). Data source: ASEAN Centre for Energy, Updated Power Development Plan (PDP) Scenario under AMS III, 2022.

Section II: Development and harmonisation of policies and regulations

Regulatory approvals

- We recognise that predictable, consistent and transparent policies and regulations regarding CBET are crucial to underpinning the bankability and long-term viability of CBET projects. Permitting requirements should be streamlined without unnecessary information requirements. Permitting decisions should also be made within well-established and predictable timeframes. There should be clear contact points and ideally a designated lead agency serving as the main interface to assist the companies involved throughout the permitting process and to coordinate with other government agencies within and across the multiple levels of government whose consent is required.

- Annex II and Annex III provide a non-exhaustive list of Australian and Singapore Government regulatory approvals that apply to CBET projects, including the legislation, relevant regulator, and specific approvals that may be required.1

- The Major Projects Help Tool can be used to help project developers identify Australian Government approvals specific to their project.2 The Major Projects Facilitation Agency (MPFA) provides information and help with Australian Government regulatory approvals and can be contacted via email at mpfa@industry.gov.au.

- We recognise that unilateral prohibitions or arbitrary restrictions to CBET will undermine investor confidence, disrupt market efficiency, increase costs, deter long-term investments in generation and transmission infrastructure, and undermine energy security. We affirm the importance of prior engagement between our Governments regarding expected changes in government policy affecting or restricting CBET, with detailed information on the scope of such measures, and with a reasonable timeframe provided for response.

Export and import facilitation

- We intend to work together to facilitate the import and export of electricity through customs procedures that are administered efficiently and promote the expeditious clearance of CBET from customs control. This includes:

- offering, to the extent practicable, electronic means to complete customs declaration and other reporting requirements applicable to the import or export of electricity between our countries;

- providing the option of electronic payment of applicable duties, taxes or other fees or charges on trade in cross-border electricity

- maintaining enquiry points to answer enquiries of governments, traders, and other interested parties on matters concerning the customs clearance of cross-border electricity.

Supporting the conduct of Cross-border subsea power cable activities

- We recognise the importance of subsea cable systems. They are the most practical method of CBET between Australia, Singapore and the region, taking into account the region's archipelagic geography and as demonstrated by the extensive network of digital subsea cables regionally and internationally.

- We also recognise the importance of a legal and regulatory framework that supports the development and transit of subsea power cables through the region's waters, starting from subsea surveys, as well as the laying, protection, maintenance and repair of subsea power cables.

Subsea surveys, and installation, maintenance and repair of subsea power cables

- We affirm the need for expeditious and efficient conduct of subsea surveys for, and installation, maintenance and repair of subsea power cable systems, to national, regional and global connectivity.

- We will endeavour to ensure that, to the extent possible, an entity which operates, owns or controls subsea cable systems has flexibility to choose suppliers of installation, maintenance or repair services.

- If either Participant considers that a measure of the other Participant affects the ability of a company of the other Participant to expeditiously and efficiently conduct surveys for, and install, maintain, repair or protect subsea cable systems, it may request consultations with the other Participant with regard to that measure. We will enter into consultations with a view to exchanging information on the operation of the measure and to considering whether further steps are necessary and appropriate.

- Where subsea surveys, or the installation, maintenance and repair of subsea power cables, take place in an area that falls under the jurisdiction of a third country, the relevant authorities of the two countries engaged in CBET may engage the authorities of the third country, as appropriate, to facilitate the necessary regulatory approvals and permits for such activities.

Vessels participating in subsea power cable activities

- We intend to maintain predictable, consistent and transparent regulatory processes to facilitate the movement of vessels to and from our respective territories, which are engaged in activities connected to the construction, repair, operation or use of cross-border electricity infrastructure. This includes:

- Pre-arrival, arrival and departure reporting of vessels entering and departing our ports

- Options to secure concessional duty treatment when engaged in the installation, repair or decommissioning of cross-border electricity infrastructure.

- Each Participant will ensure that, where a permit is required for a foreign-registered vessel to undertake conduct of surveys for, and installation, protection, maintenance or repairs of subsea cable systems that are operated, owned or controlled by a person of the foreign country in question:

- the activities for which any such permit is required are publicly available;

- the requirements and procedures for applying for any such permit, and for renewal of a permit, including the indication of agencies or authorities involved, and any relevant application documents, are publicly available;

- the criteria for assessing an application for any such permit are made available upon reasonable prior request in writing;

- the procedures for applying for any such permit and, if granted, the permit and the procedures for renewal of a permit are administered in a reasonable, objective and impartial manner;

- within a reasonable period of time after the submission of an application for any such permit and for renewal of a permit that is considered complete under its laws and regulations, it informs the applicant of the decision concerning the application;

- any such permit, if granted, is of a sufficient duration to undertake the required installation, maintenance or repairs of subsea cable systems; and

- any fee charged by any of its relevant bodies to obtain, maintain or renew any such permit is reasonable, transparent, and is limited in amount to the approximate cost of services rendered by that body in respect of any such fee.

Protection of subsea power cables

- We recognise the importance of taking steps to protect subsea power cables from damage, given the complexity, cost, and time required to correct cable faults and the implications for energy access and security. We acknowledge that beyond measures typically taken by industry (such as route selection and design to avoid areas of particular risk, cable armouring, and cable burial), governments themselves also need to take measures to enhance the protection of subsea power cables.

- We will endeavour to protect and mitigate the risk of damage to subsea cable systems that are operated, owned or controlled by a person of the other Participant, which may include, as appropriate:

- the use of geospatial alert systems;

- making information available on the location of subsea cable systems to inform mapping and charting, such as having cable routes published on up-to-date nautical charts;

- public demarcation of areas, such as cable corridors or cable protection zones, within which subsea cable systems are present and where certain activities are restricted within that area to protect subsea cable systems;

- sharing of incident data, threat information and bathymetric and seafloor data from published nautical products

- activities to promote awareness of subsea cable systems.

Upholding existing commitments

- We will uphold our respective commitments under bilateral and multilateral agreements to which we are Party, including the Singapore-Australia Free Trade Agreement, WTO Agreements and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), to enable and facilitate commercial activities that drive CBET.

- We underscore the importance of ensuring that permitting requirements for subsea power cable activities, if any, are consistent with UNCLOS. We affirm the freedoms and entitlement stated in UNCLOS regarding the laying of submarine cables in the Exclusive Economic Zone and continental shelf, and will comply with our relevant obligations regarding the laying of submarine cables under UNCLOS.

Section III: Governance

- We recognise the necessity of a robust governance framework for CBET, in order to promote accountability and transparency, as well as safeguard the rights and interests of all parties. This would in turn ensure the long-term resilience and viability of CBET projects.

Stakeholder consultation

- We recognise that early and regular engagement of relevant domestic and foreign government bodies, industry, civil society, and local communities is essential to ensure broad-based support for CBET and to efficiently resolve complaints or administrative difficulties encountered during CBET. In the case of Australia, this would include early engagement with relevant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. For subsea surveys, and the laying, maintenance and repair of subsea power cables, consultation with other maritime users is also critical to ensure the safety and resilience of subsea cable infrastructure.

- We will also ensure that updates regarding our governments' policies and plans regarding CBET are periodically communicated to the relevant stakeholders and the general public through the appropriate platforms.

Dispute resolution

- We will seek to address and resolve through amicable discussions between us and in a timely manner any relevant concerns encountered in the implementation of this Framework.

- We reaffirm our rights to have recourse to dispute resolution procedures in respect of disputes arising under applicable international trade and investment agreements to which Australia and Singapore are a party, including the Singapore-Australia Free Trade Agreement and the WTO Agreements. We also reaffirm our rights to have recourse to the compulsory and binding procedures in Part XV of UNCLOS for the settlement of disputes concerning the interpretation and application of UNCLOS.

Section IV: Renewable energy certificates (RECs) and carbon accounting

Renewable energy certificates (RECs)

- We note that there is currently no major international standard that recognises credible CBET Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) outside of single markets (e.g. the European Union). As RECs allow entities to make reliable and verifiable claims to renewable electricity use, it is important to give industry and other organisations the confidence that CBET RECs properly account for the electricity they represent and can be used to meet their sustainability commitments. Singapore and Australia will continue to cooperate on a CBET RECs Standard to ensure the credibility of CBET RECs, which will help to catalyse demand for and facilitate investments in CBET projects.

- When developing frameworks for CBET RECs, some of the factors that should be considered include:

- mutual recognition of RECs,

- selection of best practice standards

- concepts such as exclusive ownership, credible data, and prevention of double counting.

Carbon accounting

- We will continue to adopt and implement national policies that align with UNFCCC and Paris Agreement obligations. We will cooperate on the development and implementation of embedded emissions accounting in a reliable, transparent, and cost-effective manner. We will share data and best practices to improve transparency and reliability of emissions data.

- We will incorporate best practices from embedded emissions accounting protocols to ensure interoperability of embedded emissions accounting frameworks through our work together under our Green Economy Agreement and at the World Trade Organization.

- Our approaches to embedded emissions accounting will continue to facilitate our trade in downstream goods, such as those produced using renewable electricity, rather than becoming non-tariff barriers to trade.

Section V: Knowledge-sharing and partnerships

- Knowledge-sharing between government systems will be important to maximise the benefits of CBET. We intend to share information on the electricity sector as it evolves. We will also explore collaboration on scientific research and development, adoption and harmonisation of technical standards. This collaboration could include low-carbon technologies, emerging grid-related technologies including energy storage systems, financial models for interconnector development, legal and regulatory frameworks for cross-border subsea power cable activities, and climate and geopolitical developments.

Cooperation with partners

- We are committed to working with like-minded partners to advance CBET in the region, including the ASEAN Secretariat, ASEAN Centre for Energy (ACE), International Energy Agency (IEA), and International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA).

- We support ASEAN's goal of realising the ASEAN Power Grid by 2045, and welcome the value of ASEAN as a platform for members to undertake regulatory and policy coordination for CBET, as well as engage external players to mobilise the financing and technology required. For example, Australia is engaged with ASEAN Member States, the ASEAN Secretariat, and the ASEAN Centre for Energy, to provide technical assistance and build capacity to integrate regional power grids.

- We hope that the approaches covered in this Framework can assist ASEAN in addressing the policy and regulatory challenges and opportunities involved in CBET.

Scientific research

- Australia and Singapore intend to explore potential collaborative research opportunities in areas of mutual interest within CBET and clean energy development. Such discussions could serve to realise the benefits that can flow from increased CBET both within Southeast Asia and between Southeast Asia and Australia.

Duration and signature

- This Framework is understood to be in effect as of its publication and will remain so until the Participants publicly affirm that this is no longer the case.

- This Framework represents the understanding reached between the Participants and does not create any legally binding rights or obligations.

The Ministers launched this CBET Framework on 8 October 2025 at the 10th Singapore-Australia Annual Leaders' Meeting.

For the Government of Australia

Chris Bowen

Minister for Climate Change and Energy

For the Government of the Republic of Singapore

Dr Tan See Leng

Minister-in-charge of Energy and Science & Technology, Ministry of Trade and Industry

Annex I: Integration of power grids to form Australia's National Electricity Market

- The development of Australia's National Electricity Market (NEM) in the 1990s involved the integration of six sub-national electricity grids into the NEM. While those grids were within Australia and did not cross the border with another country, they were governed by sub‑national jurisdictions at the State and Territory level. Under Australia's federal system of government, the sub-national States and Territories have significant autonomy in many policy areas. New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory were responsible for their own electricity grids until the NEM.

- The process of creating the NEM and overcoming the political, economic and technical challenges therefore has parallels with Southeast Asian countries' current efforts to increase regional power connectivity by connecting the grids of various ASEAN Member States to facilitate the longer-term objective of creating a single ASEAN Power Grid.

- The formal process to develop the NEM began in 1991 with a decision by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) to establish a National Grid Management Council (NGMC) to coordinate the planning, operation and development of a competitive electricity market. COAG took this decision in response to a report tabled in 1991 by the Industry Commission which found that potentially significant increases in Australia's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) could be realised by:

- a restructuring of the electricity supply industry with the vertical separation of generation and retail from the natural monopoly elements of transmission and distribution;

- the introduction of competition into generation and retail by providing access to the transmission and distribution systems on a non-discriminatory basis;

- progressively selling publicly owned electricity generation, transmission and distribution assets to the private sector

- the enhancement and extension of the interconnected systems of New South Wales, ACT, Victoria, and South Australia to eventually include, when economically viable, the power systems of Queensland and Tasmania.

- Creation of the NEM involved:

- the introduction of a uniform single wholesale electricity market across eastern and southern Australia,

- disaggregation of the vertically integrated electricity sector into competing generators and retailers, and monopoly transmission and distribution network service providers,

- the passage of a National Electricity Law as cooperative legislation across the participating jurisdictions to enable the NEM to operate with harmonised laws and regulations including a National Electricity Code that defines the rules for the wholesale electricity market and access to the networks;

- the establishment of the National Electricity Code Administrator (NECA) as an independent company responsible for managing changes to market rules and the network access regime;

- the establishment of the National Electricity Market Management Company (NEMMCO) as the market operator and power system operator for the NEM

- customer choice in electricity supplier across the NEM, initially for large customers, which was a first step in the transition to full retail competition and the deregulation of retail pricing.

- In a subsequent review of the NEM, senior Australian officials involved in its creation identified the following lessons:

- The material problems were defined and clear reform objectives were set

- In embarking on the reform of the electricity sector, clear objectives for change were defined and the change approach was transparent. The economic and policy implications, commercial and financial impacts, and technical and operational impacts were brought into alignment. This alignment was maintained throughout the process and has underpinned the NEM's durability.

- Reform took high-level political drive; provision of time, energy and, according to many reform participants, financial incentives

- Ministers involved in the reform were required to make a significant commitment of personal time in order to make things happen and keep the process on a consistent path.

- In the energy sector, the National Competition Payments1 had three benefits: first, the State Governments had an incentive to change as they wanted the payments; second, there was a political cost if some payments were seen to be withheld; and third, they could use the payments as an argument to undertake reform in the face of opposition. Looking to future reform, there are risks that the incentive becomes payment maximisation, rather than policy optimisation; and the relationship between the Commonwealth and the states changes from a partnership to a quasi contract. Incentive payments are not a substitute for mutual commitment to policy outcomes.

- Strategies were developed to enhance confidence in the reforms

- Confidence in the proposed reforms was developed by specifying market designs and rules in detail and then taking the time to run trial simulations and model the reforms with the involvement of the key industry and government representatives to iron out design flaws. Reforms were implemented at the state level before moving to full national reforms. The learning from these state experiences was invaluable and boosted confidence in the reforms.

- Strong and appropriate support structures were established with key stakeholder participation

- Reform across the Commonwealth and the States required significant collaboration and cooperation. Establishment of appropriate governance structures across federal, jurisdictional and industry levels was essential to ensure the reform had appropriate coordination of policy, technical design and implementation.

- It was important to give credibility to the process. This was enhanced by having an independent, highly regarded chair. The people who were involved understood the commercial realities of the businesses and the impacts of the reform on them.

- The pace of the reform allowed for effective consultation across all stakeholders

- It was important to ensure the time allowed for reform was manageable and realistic for all involved.

- The reform was managed so that the key things were done early, such as setting agreed principles and conceptual design for the market mechanisms. Ensuring there were incremental implementation steps and delivery of incremental benefits helped keep stakeholders engaged on the longer journey.

- Identifying the key stakeholders and having open and ongoing dialogue helped to build trust and engagement.

- Getting the industry structures right was key for effective competition

- The process highlighted that competitive markets only work well with a competitive industry structure.

- It also demonstrated there is an explicit trade-off between the benefits of a competitive industry structure and maximising sales proceeds from privatisation. The gains for the economy of a competitive industry structure needs to take precedence over the fiscal impacts of privatisation. To do otherwise poses a risk to the benefits of the reform being sustained.

- The material problems were defined and clear reform objectives were set

Annex II: Australia's guidelines on regulatory approvals for Cross-Border Electricity Trade

Introduction

1.1 This guidance has been developed to assist proponents of CBET projects to navigate a non-exhaustive list of approvals required under Australian Government legislation. Both project location(s) and the nature of a project can influence the regulatory approvals required for a project. While this guidance seeks to cover Australian Government approvals likely to apply to a CBET project, every project is unique and may require additional approvals to those outlined.

1.2 Australia consists of three levels of government, federal, state or territory, and local government. This list does not include regulatory approvals of state or territory governments, nor does it include local government regulatory approvals.

1.3 A typical project stage approach has been taken to illustrate the recommended sequencing between the various regulatory approvals and project stages over the life of a CBET project. Some approvals may be applicable to more than one stage depending on a project's activities and scheduling.

Disclaimer

1.4 The purpose of this publication is to assist proponents of CBET projects to navigate approval processes under Australian Government legislation.

1.4.2 The Commonwealth as represented by the Department of Industry, Science and Resources has exercised due care and skill in the preparation and compilation of the information in this publication.

1.4.3 The Commonwealth does not guarantee the accuracy, reliability or completeness of the information contained in this publication. Interested parties should make their own independent inquires and obtain their own independent professional advice prior to relying on, or making any decisions in relation to, the information provided in this publication.

1.4.4 The Commonwealth accepts no responsibility or liability for any damage, loss or expense incurred as a result of the reliance on information contained in this publication. This publication does not indicate commitment by the Commonwealth to a particular course of action.

1.4.5 It remains the responsibility of proponents to ensure compliance with all legal requirements for a project.

1. Site Selection

The site selection stage of a typical CBET project involves identifying and evaluating the most suitable locations for the land-based and sea-based components of the project to take place. This stage often involves surveys and investigations to assess the suitability of potential locations. In this stage, vessels may be required to conduct marine surveys to assess seabed conditions along proposed subsea cable routes.

| Regulator | Approval/obligation (legislation) | Details of approval/obligation |

|---|---|---|

The Treasury Australian Taxation Office | Foreign investment approval and asset registration (Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act 1975) |

|

| Department of Home Affairs | Visa sponsorship approval Working and/or maritime crew visas (Migration Act 1958) |

|

| Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW) | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander heritage protection (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984) |

|

| Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA) | Fisheries stakeholders consultation (Fisheries Management Act 1991) |

|

| Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) | Radiocommunications licencing (Radiocommunications Act 1992) |

|

| Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (DAFF) | Ballast water management plan and certificate (Biosecurity Act 2015) |

|

| Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) | Seafarer, maritime labour, maritime safety, pollution and tonnage certificates (Navigation Act 2012) |

|

| Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) | Domestic commercial vessel requirements (Marine Safety (Domestic Commercial Vessel) National Law Act 2012) |

|

| Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) | Anti-fouling certificate or declaration (Protection of the Sea (Harmful Anti-fouling Systems) Act 2006) |

|

| Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) | Ship-based sea pollution record books, management plans and emergency plans (Protection of the Sea (Prevention of Pollution from Ships) Act 1983) |

|

| Critical Infrastructure Security Centre (CISC) | Ship security plan and international ship security certificate (Maritime Transport and Offshore Facilities Security Act 2003) |

|

| National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority (NOPSEMA) | Consent to enter a petroleum or greenhouse gas safety zone or the area to be avoided (Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2006) |

|

| Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications, Sport and the Arts (DITRDCSA) | Coastal trading licence (Coastal Trading (Revitalising Australian Shipping) Act 2012) |

|

2 Feasibility

The feasibility stage of a typical CBET project involves assessing whether the project is viable and able to successfully proceed once sites are chosen. This stage focuses on designing the project with site-specific parameters taken into consideration. In this stage, technical, financial, regulatory, environmental and operational feasibility are analysed. Approvals required prior to commencement of construction are also obtained in this stage of a project.

Consultation with stakeholders should be undertaken during this stage to identify and consider the existing rights of relevant existing uses or users in the proposed licence area if not already commenced during the site selection stage, including but not limited to:

- Local communities

- Fisheries stakeholders (Fisheries Management Act 1991)

- Native title holders or claimants (Native Title Act 1993)

- If applicable, shipping stakeholders

- If applicable, stakeholders for Defence Aviation Areas (Defence Act 1903)

- If applicable, stakeholders for prescribed airspace (Airports Act 1996)

- If applicable, telecommunications carriers for existing submarine cables within submarine cable protection zones (Telecommunications Act 1997 – Schedule 3A)

- If applicable, tourism stakeholders

- If applicable, stakeholders for petroleum or greenhouse gas safety zones or the area to be avoided (Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2006)

All approvals listed in the site selection stage may also apply to the feasibility stage if not already obtained during site selection.

Additional approvals required during the feasibility stage are tabled below.

| Regulator | Approval/obligation (legislation) | Details of approval/obligation |

|---|---|---|

| Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW) | Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation approval (Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999) |

|

| Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW) | Sea dumping permit (Environment Protection (Sea Dumping) Act 1981) |

|

| Parks Australia | Australian Marine Park authorisation (Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999) |

|

| National Native Title Tribunal | Native title compliance and agreement (Native Title Act 1993) |

|

| Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW) | Underwater cultural heritage permit (Underwater Cultural Heritage Act 2018) |

|

| Offshore Infrastructure Registrar | Transmission and infrastructure licence (Offshore Electricity Infrastructure Act 2021) |

Licence holders must submit annual reports to the Offshore Infrastructure Registrar over the course of the term of the TIL, providing details on ongoing compliance with the merit criteria. Licence holders are also required to report specified events in relation to the TIL to the Offshore Infrastructure Regulator as soon as practicable after the event occurs. The following approvals should be obtained and obligations undertaken prior to applying for a TIL as applicable to the project:

|

| Australian Industry Participation Authority | Australian Industry Participation plan (Australian Jobs Act 2013) |

|

| Offshore Infrastructure Regulator | Offshore electricity infrastructure management plan and associated requirements (Offshore Electricity Infrastructure Act 2021) |

The following approvals should be obtained and obligations met (as relevant to the project) prior to applying for approval for an offshore electricity infrastructure management plan:

|

| Offshore Infrastructure Regulator | Work health and safety approvals (Offshore Electricity Infrastructure Act 2021 |

|

| Department of Defence | Defence export permit (Customs Act 1901 and Defence Trade Controls Act 2012) |

|

| Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) | Submarine cable installation permits and undertaking restricted activities within a submarine cable protection zone (Telecommunications Act 1997 (Schedule 3A)) |

|

| Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications, Sport and the Arts (DITRDCSA) | Prescribed airspace intrusion approval (Airports Act 1996) |

|

| Department of Defence | Approval for proposed constructions or objects in a Defence Aviation Area (Defence Act 1903) |

|

| Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (DAFF) | Biosecurity import permits and biosecurity obligations (Biosecurity Act 2015) |

|

| Australian Border Force (ABF) | Customs clearance and reporting requirements (Customs Act 1901) |

|

3. Construction

The construction stage of a typical CBET project involves installing submarine cables and land or sea-based electricity generation, transmission and storage infrastructure. Equipment, materials and the construction workforce are mobilised during this stage.

The following regulatory approvals may have been obtained in previous stages but may be required in the construction stage if not already obtained and maintained during previous stages:

- Foreign investment approval and asset registration

- Working and/or maritime crew visas and sponsorship approval

- Customs clearance and reporting requirements

- Radiocommunications licencing

- Ballast water management plan and certificate

- Seafarer, maritime labour, maritime safety, pollution and tonnage certificates

- Domestic commercial vessel requirements

- Anti-fouling certificate or declaration

- Ship-based sea pollution record books, management plans and emergency plans

- Ship security plan and international ship security certificate.

- Consent to enter a petroleum or greenhouse gas safety zone or the area to be avoided

- Coastal trading licence

- Prescribed airspace intrusion approval

- Biosecurity import permits and obligations

- Customs clearance and reporting requirements.

Additional approvals required during the construction stage are tabled below

| Regulator | Approval/obligation (legislation) | Details of approval/obligation |

|---|---|---|

| Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW) | Hazardous waste permit (Hazardous Waste (Regulations of Exports and Imports) Act 1989) |

|

| National Heavy Vehicle Regulator (NHVR) | Heavy Vehicle National Law access permit (Heavy Vehicle National Law) |

|

| Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) | National Electricity Market registration (National Electricity Law) |

|

| Critical Infrastructure Security Centre | Critical infrastructure registration, risk management program and reporting (Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018) |

|

4. Operation

The operation stage of a typical CBET project involves an active system that starts transmitting electricity between countries. This involves commissioning and testing, system monitoring and control, and regulatory and market operations. Ongoing notification and reporting requirements apply during this stage.

The following regulatory approvals may have been obtained in previous stages but may be required in the operation stage if not already obtained and maintained during previous stages:

- Foreign investment approval and asset registration

- Working and/or maritime crew visas and sponsorship approval

- Customs clearance and reporting requirements

- Radiocommunications licencing

- Ballast water management plan and certificate

- Seafarer, maritime labour, maritime safety, pollution and tonnage certificates

- Domestic commercial vessel requirements

- Anti-fouling certificate or declaration

- Ship-based sea pollution record books, management plans and emergency plans

- Ship security plan and international ship security certificate

- Consent to enter a petroleum or greenhouse gas safety zone or the area to be avoided

- Coastal trading licence

- Prescribed airspace intrusion approval

- Critical infrastructure registration, risk management program and reporting

- Hazardous waste permit

- Heavy Vehicle National Law access permit

Additional approvals required in the operation stage are tabled below.

| Regulator | Approval/obligation (legislation) | Details of approval/obligation |

|---|---|---|

| Clean Energy Regulator | Renewable electricity facility (Guarantee of Origin) registration and certificates (Future Made in Australia (Guarantee of Origin) Act 2024) |

|

| Clean Energy Regulator (CER) | National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting scheme registration and reporting (National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Act 2007) |

|

5. Decommissioning

The decommissioning stage of a typical CBET project involves safety dismantling and retiring project infrastructure once it reaches the end of its operational life. Any reporting and notification obligations attached to the decommissioning stage may continue into post-decommissioning.

The following regulatory approvals may have been obtained in previous stages but may be required in the operation stage if not already obtained and maintained during previous stages:

- Foreign investment approval and asset registration

- Working and/or maritime crew visas and sponsorship approval

- Customs clearance and reporting requirements

- Radiocommunications licencing

- Ballast water management plan and certificate

- Seafarer, maritime labour, maritime safety, pollution and tonnage certificates

- Domestic commercial vessel requirements

- Anti-fouling certificate or declaration

- Ship-based sea pollution record books, management plans and emergency plans

- Ship security plan and international ship security certificate

- Consent to enter a petroleum or greenhouse gas safety zone or the area to be avoided

- Coastal trading licence

- Prescribed airspace intrusion approval

- Sea dumping permit

- Hazardous waste permit

- Heavy Vehicle National Law access permit

Annex III: Singapore's guidelines on regulatory approvals for large-scale electricity imports

Introduction

1. The Energy Market Authority (the "Authority") has identified electricity imports as a strategic energy initiative for Singapore, to enhance our future energy security, sustainability, and affordability. The Authority is also the lead agency for facilitating the entry of around 6 Gigawatts (GW) of low-carbon electricity imports into Singapore by 2035.

1.2 EMA adopts a three-stage process to facilitate the entry of electricity imports into Singapore.

1.2.1 A Conditional Approval is granted to an importer when EMA preliminarily assesses that the proposed electricity import project is technically and commercially viable. The Conditional Approval facilitates the companies in obtaining the necessary regulatory approvals and licences for its project.

1.2.2 EMA may thereafter grant a Letter of Conditional Licence to projects that have met the conditions set out by EMA in the Conditional Approval, such as conducting further studies and engaging relevant countries.

1.2.3 Following the award of a Conditional Licence, the parties are expected to advance towards finalising the required studies and discussions in relation to the commercial, technical, environmental, regulatory and financial aspects of the project. Each of these aspects must be finalised for a project to eventually achieve financial close, and EMA to confirm that the project has fulfilled all requirements to be granted a final Importer Licence. With the Importer Licence, the project is ready to commence construction and operations.

1.3 While information on available public landing sites will be provided to importers and/or grid operator(s) for pre-planning purposes, importers should perform pre-consultations with SP PowerGrid Limited (SPPG) and key government agencies only after the issuance of the conditional award.

1.4 This set of Guidelines is intended to provide importers who will be developing dedicated connections from source to local grid and grid operator an overview of the process for obtaining the necessary approvals and permits, in 5 broad stages with a non-exhaustive list of government agencies to be consulted, for the deployment of large-scale electricity imports up to the award of import licence. They are as follows:

I. Issuance of Letter of Conditional Licence

- Letter of Conditional Licence to be issued as precursor to subsequent stages of regulatory processes

| Agencies to be consulted | Overview of the process |

|---|---|

| Energy Market Authority (EMA) |

|

II. Pre-consultations

Technical Pre-consult

- Supply-related plan including but not limited to proposed import source, supply capacity, supply profile etc

- Infrastructure-related plan including but not limited to proposed sea corridor approach, landing site, cable routing, grid connection etc

- Pre-feasibility for subsequent landuse consultations with individual agencies1 and overall planning approval

- Attain In-Principle No Objection (IPNO) from EMA and SPPG as precursor for subsequent landuse consultations with agencies. In-Principle No Objection (IPNO) from agencies to the proposed developments would form the precursor to planning approval from URA. This list of agencies is by no means exhaustive.

Landuse Pre-consult

- Landuse consultations with individual agencies1 and/or public or private land-owners for seabed/ foreshore/ inland

- Obtain information and parameters necessary including but not limited to as-built plans, planning parameters, site-specific conditions etc, if necessary. Agencies may require requesting parties to enter into a non-negotiable non-disclosure agreement ("NDA") prior to any disclosure of site information. This will be at the discretion of the relevant agencies.

- Attain In-Principle No Objection (IPNO) from agencies as precursor for overall planning approval. In-Principle No Objection (IPNO) from agencies to the proposed developments would form the precursor to planning approval from URA. This list of agencies is by no means exhaustive.

| Agencies to be consulted | Overview of the process |

|---|---|

| Energy Market Authority (EMA) |

For onward consultations with SPPG and PowerGas

|

| Singapore Power Power Grid (SPPG) |

|

| Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) |

|

| Maritime Port Authority (MPA) |

|

| National Parks Board (NParks) |

|

| Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA) |

|

| National Environment Agency (NEA) |

|

| Singapore Food Agency (SFA) |

|

| Singapore Land Authority (SLA) – for development on state-land |

|

| Land Transport Authority (LTA) |

|

| Public Utilities Board (PUB) |

|

Jurong Town Corporation (JTC)

– for Jurong Island and industrial sites under JTC's management |

|

Civil Aviation Authority of Singapore (CAAS)

– for sites within airport(s) planning area under CAAS's jurisdiction |

|

Housing Development Board (HDB) or

– for sites earmarked for reclamation to be carried out by HDB or JTC |

|

Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA)

– for fire safety & HAZMAT clearances by SCDF |

|

| Building and Construction Authority (BCA) |

|

III. Planning Approval

- When all IPNOs are obtained, to obtain Planning Approval from URA, Approval from MPA

- Attain approval for foreshore or marine development (s) from MPA

- Enter into the necessary Wayleave and or TOL arrangements for site occupation.

| Agencies to be consulted | Overview of the process |

|---|---|

| Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) |

|

| Maritime Port Authority (MPA) |

|

| Singapore Land Authority (SLA) – for development on state-land |

|

| Private Land owners |

|

IV. Development Control (DC) for commencement of works

- Upon Planning Approval ie Written Permission (WP), onward submission to URA and relevant authorities for CORENET Submission for Development Control Approvals (DC) by Qualified Persons (QP).

- Attain Development Control (DC) Approvals for work commencement from the relevant agencies

| Agencies to be consulted | Overview of the process |

|---|---|

| Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) |

|

| Building and Construction Authority (BCA) |

|

V. Issuance of Import Licence

- Upon meeting all Condition Precedents, Import Licence will be issued to importer

| Agencies to be consulted | Overview of the process |

|---|---|

| Energy Market Authority (EMA) |

|

Footonote

1 Australia consists of three levels of government, Federal, State or Territory, and local government. Australia's list in Annex II is a non-exhaustive list of Australian Government regulatory approvals that may apply to a CBET project. Both project location(s) and the nature of a project can influence the regulatory approvals required for a project. This list does not include regulatory approvals of state or territory governments, nor does it include local government regulatory approvals.

2 Information is available at: https://business.gov.au/expertise-and-advice/major-projects-facilitatio….