Australia and the United Nations is an authoritative, single volume appraisal of Australia's engagement with the United Nations.

The book brings together distinguished academics and historians in the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade in an account of the part that Australia has played in the United Nations from its involvement in the League of Nations and the foundation of the United Nations to the second decade of the twenty-first century.

Chapter authors examine Australia's contribution to the UN's roles in international security, peacekeeping, and disarmament; its evolving policy to UN efforts to promote self-rule and independence for dependent territories; its contribution to the work of the UN specialised agencies and the efforts of the wider UN family to promote development; and its engagement with the United Nations on environmental matters, human rights and international law.

The final chapter critically examines Australia's efforts to reform the United Nations.

Appendixes include descriptions of the Australian Permanent Missions to the United Nations and biographies of the Australian Permanent Representatives in New York.

© Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 2012

Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights) in this publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. With the exception of the Coat of Arms, and where otherwise noted, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence. The details of the licence conditions are available on the Creative Commons website, as is the full legal code for the CC BY 3.0 AU licence.

At the time of publishing all URLs were correct but may change in time.

National Library Catalogue-in-Publishing entry

Australia and the United Nations/ edited by James Cotton and David Lee

ISBN: 9781743220160 (hbk.)

9781743220177 (pbk.)

Includes index.

Bibliography.

United Nations–Australia

Australia–Foreign Relations

Other authors/contributors: Cotton, James, 1949–

Lee, David, 1965–

Australia. Dept. of Foreign Affairs and Trade

341.2394

Book production by

Longueville Media

The Australian Minister for External Affairs and Attorney-General, Dr HV Evatt, signs the Charter of the United Nations on behalf of Australia, watched by the Australian Deputy Prime Minister, Francis M Forde (right), San Francisco, 26 June 1945. [UN Photo/McLain]

A key point in the foreign policy of Australia is enthusiastic and sustained activity in all aspects of the work of the United Nations.

…

It is the best presently available instrument, both for avoiding the supreme and ultimate catastrophe of a third world war, waged with all-destroying weapons, and also for establishing an international order which can and should assure to mankind security against poverty, unemployment, ignorance, famine and disease

…

We shall continue steadfastly and courageously to play our part in this Organisation, on which must rest most of the hopes of men of good will throughout the world.

– Statement to the House of Representatives on Foreign Affairs by the Right Hon. Dr HV Evatt, Minister for External Affairs, 13 March 1946.

Contents

James Cotton

Neville Meaney

David Lee

Matthew Jordan

Peter Carroll

Chad Mitcham

Moreen Dee

Matthew Jordan

Lorraine Elliott

Colin Milner

Roderic Pitty

Acronyms and abbreviations used in Notes and Bibliography

Appendix 1

Jeremy Hearder

Appendix 2

Jeremy Hearder

Editors

James Cotton, Emeritus Professor of Politics, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of New South Wales, Australian Defence Force Academy.

David Lee, Director, Historical Publications and Information Section, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Contributors

Peter Carroll, Professor and Senior Research Fellow, Faculty of Business, University of Tasmania.

Moreen Dee, Executive Officer, Historical Publications and Information Section, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Lorraine Elliott, Professor, Department of International Relations, School of International, Political and Strategic Studies, Australian National University.

Jeremy Hearder, Consultant, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Matthew Jordan, Executive Officer, Historical Publications and Information Section, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Neville Meaney, Honorary Associate Professor of History, University of Sydney.

Colin Milner, Director, Pacific Program, Counter-Terrorism Branch, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade; formerly Director, Human Rights and Indigenous Issues, and International Law and Transnational Crime Sections.

Chad Mitcham, Consultant, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Roderic Pitty, Associate Professor and Chair, Politics and International Relations, School of Social and Cultural Studies, University of Western Australia.

Foreword

It gives me great pleasure to welcome the publication, Australia and the United Nations, a book produced under the auspices of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The project has been researched and written by a team of historians, both academics and departmental officers, engaged by the Historical Publications and Information Section of the Department.

The book records Australia's engagement with the United Nations, an engagement which goes back to its formation and to the convening of the first UN Security Council. It also covers our involvement with the organisation which preceded the United Nations, the League of Nations.

It tells a story of bipartisan commitment to the United Nations over more than sixty-five years. It also provides an account of Australia's contributions to the formation and operations of the United Nations and our role in many of its achievements.

As the book shows, Australian Minister for External Affairs HV Evatt and his staff played a vital role in the framing of the UN Charter. We held the first presidency of the UN Security Council, and provided the first peacekeepers a year later.

We have made a sustained contribution over the years to the goal of promoting disarmament and non-proliferation, from the Chemical Weapons Convention to the International Commission on Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament. We have supported the efforts of the broader UN family to promote the development of less developed countries and we have a strong record of involvement with the UN specialised agencies.

We were one of the eight countries which drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and have since striven to strengthen international law to prevent armed conflict and to promote individual human rights against states which have threatened them. We also played an active part in the negotiation of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Australians have been long engaged in efforts to reform the UN organisation to make it work better for the international community, from HV Evatt's efforts to modify the Security Council veto to Gareth Evans's championing of the 'responsibility to protect'. In the more recent era of UN history, Australia has worked energetically to achieve a global solution to the challenges of climate change.

In producing this work, a number of historians were asked to review the documentary record, and were given access where appropriate to official records, in order to tell the story as they saw it. The only standards that were applied were scholarly.

The record that they have produced of Australia's significant part in UN history stands for itself. I commend the publication of this history of Australia and the United Nations.

Bob Carr

Minister for Foreign Affairs

Acknowledgements

This volume was written by historians based in the Historical Publications and Information Section of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and academic specialists who were invited by the Department to write on their areas of expertise. The book was edited by James Cotton, Emeritus Professor of Politics, University of New South Wales, and David Lee, Director, Historical Publications and Information Section, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The authors of individual chapters are listed on the contents page. In addition to authoring Chapter 6, 'Australia and development cooperation at the United Nations', Chad Mitcham was a researcher for Chapter 5, 'Australia, ECOSCOC and the UN specialised agencies'. Jeremy Hearder interviewed past and former ministers and departmental officials connected with Australian engagement with the United Nations and compiled Appendixes 1 and 2. Matthew Jordan compiled the Bibliography.

Officers from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the Department of Agriculture Fisheries and Forestry, the Attorney-General's Department, the Treasury, the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations, the Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID), the Department of Health and Ageing, and the Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency provided expert comments on draft chapters. The authors of the chapters, however, assume full responsibility for the conclusions, opinions and arguments in this study, such opinions not representing the views of past Australian governments or the current government of the Commonwealth.

The editors and authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance in researching the book of Chris Ritchie, Tamas Uhrin, Rob Schaap, Gregory Pemberton, Adam Henry and Barbara Fothergill. Project members received valuable assistance from the staff of the National Archives of Australia, the National Library of Australia, the Mitchell Library and Melbourne University Archives in locating records. In the H.V. Evatt Library, DFAT, we would like to extend a special thanks to Marisa Vearing, Jenny Ensbey and Robyn Rooney for their constant help and forbearance.

The Australian Institute of International Affairs (AIIA) jointly with the Historical Publications and Information Section of the Department convened a Forum on the history of Australia and the United Nations on 1 and 2 February 2011 to assist in the writing of the book. For organising and presiding over the Forum the editors and authors especially thank John McCarthy AO, National President, Melissa Conley-Tyler, Chief Executive Officer, John Robbins, National Deputy Director, Shirley Scott, National Research Director, and research interns Ashley Jenkins and Naomi von Dinklage of the AIIA. For presenting key-note addresses they thank Richard Woolcott AC, Professor the Hon Robert Hill AC, James Ingram AO and Professor Charles Sampford. Generally they thank all serving officials of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and other agencies who attended the Forum or provided comments to authors. The United Nations Information Centre for Australia, New Zealand and the South Pacific and its Director, Christopher Woodthorpe, gave invaluable assistance to the project throughout and members of the United Nations Association of Australia kindly attended the forum.

The editors and authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of all the following who either attended the Forum on the book on 1 and 2 February 2011, read drafts, provided general comments or were interviewed for the volume: Professor Philip Alston, HD Anderson AO, Dame Margaret Joan Anstee, Howard Bamsey PSM, Bill Barker, Bruce Davis AM, Professor Joan Beaumont, Anthony Billingsley, Dr Neal Blewett AC, Professor Frank Brennan SJ AO, Richard W. Butler AC, Henry Burmester QC, Colin Chapman, Professor Hilary Charlesworth AM, Denise Conroy, Meghan Cooper, John Dauth LVO, Ian Dudgeon, Professor the Hon. Gareth Evans AO, James Gibson, the late Hugh Gilchrist, Professor the Hon. Robert M. Hill AC, Heather Henderson, Peter Henderson AC, Professor David Horner AM, James Ingram AO, Kim Jones AM, Robert Jauncey, Andrew Leask, Jane Madden, Mary Johnson, Professor John Langmore, Angus MacDonald, Julie McKay, Nina Markovic, Geoff Miller AO, Rachel Miller, John Monfries, Charles Mott, Satya Nandan CF CBE, John Nethercote, Annmaree O'Keefe, Kevin Playford, Daniel Purnell, Connor Quinn, Charles Radcliffe, Dayle Redden, Jonas Rey, Roland Rich, Lindsay Ritchie, John Sanderson AC, Elizabeth Shaw, Emeritus Professor Ivan Shearer AM RFD, Chris Sidoti, Mike Smith, Natasha Smith, Douglas Sturkey CVO AM, the UN Women (Australia), Ron A Walker, Pera Wells, Her Excellency Penelope Wensley AC, Thom Woodroofe and Michael J. Wilson. Special thanks are due to Richard Woolcott AC, who read the whole manuscript in draft.

Moreen Dee prepared all the illustrations published in this book. For assistance with photographs and kind permission to publish we gratefully acknowledge: Frehiwot Bekele and staff at the UN Photo Library; the League of Nations Archives; the International Labour Organization; the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization; the World Health Organization; the World Intellectual Property Organization; the World Bank Archives; the International Institute for Sustainable Development; The National Film Board of Canada; the US State Department; the National Archives of Australia; the National Library of Australia; the Australian War Memorial; the Department of Health and Ageing; the Department of Defence; the Australian Federal Police; the New South Wales Police Force; the University of Melbourne Archives; Flinders University South Australia; the State Library of Western Australia; Robyn Hodgkin and Lauren Stasinowsky from the Australian Permanent Mission to the United Nations in Geneva; and Lisa Sharland and Barry Chapman from the Australian Permanent Mission to the United Nations in New York. For permission to reproduce photographs in their collections, our thanks are due to Professor James Cotton, James Ingram AO, Mrs Margaret Kelly, the Hon. David Kemp, the McDougall Family, Charles and Beth Mott, Lieutenant-General John Sanderson AC (retd), the Hon. Tony Street, Dr Wendy Way and Richard Woolcott AC.

Sarah Shrubb gave invaluable help in style editing the manuscript. From Longueville Media we thank David Longfield, Elmandi du Toit, and Lucie Stevens for their production, design and editing to produce this book.

Acronyms and abbreviations

| AAEC | Australian Atomic Energy Commission |

| ACC | Administrative Committee for Coordination |

| ADAB | Australian Development Assistance Bureau |

| ADB | Asian Development Bank |

| ADF | Australian Defence Force |

| AEC | Atomic Energy Commission |

| AFP | Australian Federal Police |

| AIDEP | Asian Institute for Economic Development and Planning |

| AIF | Australian Imperial Force |

| AIIA | Australian Institute of International Affairs |

| ALP | Australian Labor Party |

| ANZUS | Australia, New Zealand and the United States |

| APEC | Asia–Pacific Economic Cooperation (Forum) |

| ATSIC | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission |

| AusAID | Australian Agency for International Development |

| AWB | Australian Wheat Board |

| BIS | Bank for International Settlements |

| BWC | Biological Weapons Convention |

| CAME | Conference of Allied Ministers of Education |

| CBD | Convention on Biological Diversity |

| CCM | Convention on Cluster Munitions |

| CCOP | Coordinating Committee for Offshore Prospecting |

| CCP | Chinese Communist Party |

| CD | Conference on Disarmament |

| CEB | Chief Executives Board for Coordination |

| CEDAW | Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women |

| CFB | Combined Food Board |

| CHR | Commission on Human Rights |

| CPA | Coalition Provisional Authority |

| CSD | Commission on Sustainable Development |

| CSIRO | Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation |

| CTBT | Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty |

| CWC | Chemical Weapons Convention |

| DAC | Development Assistance Committee of the OECD |

| DAFF | Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry |

| DEA | Department of External Affairs |

| DFA | Department of Foreign Affairs |

| DFAT | Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade |

| DK | Democratic Kampuchea |

| DPKO | Department of Peacekeeping Operations |

| DPWR | Department of Post-War Reconstruction |

| DRC | Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| ECAFE | UN Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East |

| (see also UNESCAP) | |

| ECOSOC | UN Economic and Social Council |

| ENDC | Eighteen-Nation Disarmament Committee |

| EPTA | UN Expanded Programme of Technical Cooperation |

| EU | European Union |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| FEAC | Financial and Economic Advisory Committee |

| FFYP | first five-year plan |

| FIAS | Foreign Investment Advisory Service |

| FRETILIN | Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor |

| FSF | Financial Stability Fund |

| FUNDWI | UN Fund for the Development of West Irian |

| GAB | General Arrangements to Borrow |

| GATS | General Agreement on Trade in Services |

| GATT | General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade |

| GDP | gross domestic product |

| GEF | Global Environment Facility |

| GEMS | Global Environmental Monitoring System |

| GOC | Security Council Committee of Good Offices |

| HRC | Human Rights Council |

| IAEA | International Atomic Energy Agency |

| IBRD | International Bank for Reconstruction and Development |

| ICAO | International Civil Aviation Organization |

| ICC | International Criminal Court |

| ICER | Interdepartmental Committee on External Relations |

| ICJ | International Court of Justice |

| IDA | International Development Association |

| IEFC | International Emergency Food Council |

| IEFR | International Emergency Food Reserve |

| IFAD | International Fund for Agricultural Development |

| IFC | International Finance Corporation |

| ILC | International Law Commission |

| ILO | International Labour Organization |

| IMF | International Monetary Fund |

| INF | intermediate-range nuclear forces |

| INFOSAN | International Food Safety Authorities Network |

| INFOTERRA | International Environmental Information System |

| INTERFET | International Force for East Timor |

| IPR | Institute of Pacific Relations |

| ISF | International Stabilisation Force (Timor-Leste) |

| ITO | International Trade Organization |

| JPC | Joint Planning Committee |

| JSCOT | Joint Standing Committee on Treaties |

| JUSCANZ | Japan, the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand group |

| LDCs | least developed countries, less developed countries |

| LNG | liquefied natural gas |

| LNU | League of Nations Union |

| MAD | Mutual Assured Destruction |

| MDGs | Millennium Development Goals |

| MEAs | multilateral environmental agreements |

| MESC | Anglo-American Middle East Supply Centre |

| NAB | New Arrangements to Borrow |

| NATO | North Atlantic Treaty Organization |

| NCC | National Consultative Committee (of the WSSD, 1995) |

| NEI | Netherlands East Indies |

| NGO | non-government organisation |

| NIEO | New International Economic Order |

| NPT | (Nuclear) Non-Proliferation Treaty |

| NPTREC | NPT Review and Extension Conference |

| NWS | nuclear weapons states |

| OCHA | Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs |

| ODA | official development assistance |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| OEED | Organisation for European Economic Development |

| ONUC | UN Operation in the Congo |

| OPEC | Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries |

| PCIJ | Permanent Court of International Justice |

| PKI | Partai Komunis Indonesia/Indonesian Communist Party |

| PNG | Papua New Guinea |

| PRC | People's Republic of China |

| PRK | People's Republic of Kampuchea |

| PTBT | Partial Test Ban Treaty |

| RAMSI | Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands |

| SALT | Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty |

| SEAC | South-East Asia Command |

| SNC | Supreme National Council (Cambodia) |

| SOC | State of Cambodia |

| SPS | Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures |

| START | Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty |

| SUNFED | UN Special Fund for Economic Development |

| TBT | Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade |

| TPNG | Territory of Papua and New Guinea |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| UNAMET | UN Mission in East Timor |

| UNAMIC | UN Advance Mission in Cambodia |

| UNCCD | UN Convention to Combat Desertification |

| UNCED | UN Conference on Environment and Development |

| UNCHE | UN Conference on the Human Environment |

| UNCIO | UN Conference on International Organization |

| UNCIP | UN Commission for India and Pakistan |

| UNCLOS I | UN Conference on the Law of the Sea 1958 |

| UNCOK | UN Commission on Korea |

| UNCTAD | UN Conference on Trade and Development |

| UNCURK | UN Commission for the Unification and Rehabilitation of Korea |

| UNDOF | UN Disengagement Force (Golan Heights) |

| UNDP | UN Development Programme |

| UNEF | UN Emergency Force (Middle East) |

| UNEP | UN Environment Programme |

| UNESCAP | UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific |

| UNESCO | UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| UNFCCC | UN Framework Convention on Climate Change |

| UNFICYP | UN Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus |

| UNGA | UN General Assembly |

| UNHCR | UN High Commissioner for Refugees |

| UNICEF | UN Children's Fund |

| UNICPOLOS | UN Informal Consultative Process on Oceans and the Law of the Sea |

| UNIDO | UN Industrial Development Organization |

| UNIFEM | UN Development Fund for Women |

| UNIFIL | UN Interim Force in Lebanon |

| UNMAC | UN Military Armistice Commission in Korea |

| UNMISET | UN Mission of Support in East Timor |

| UNMIT | UN Integrated Mission in Timor-Leste |

| UNMOGIP | UN Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan |

| UNMOVIC | UN Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission |

| UNO | UN Organization |

| UN-OCEANS | UN Oceans and Coastal Areas Network |

| UNOTIL | UN Office in Timor-Leste |

| UNPROFOR | UN Protection Force in Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Macedonia |

| UNRIP | UN Representative in India and Pakistan |

| UNRRA | UN Relief and Rehabilitation Agency |

| UNSC | UN Security Council |

| UNSCOM | UN Special Commission |

| UNSCR | UN Security Council Resolution |

| UNSSOD | UN Special Session on Disarmament |

| UNTAC | UN Transitional Authority in Cambodia |

| UNTAET | UN Transitional Administration in East Timor |

| UNTAG | UN Transition Assistance Group (Namibia) |

| UNTCOK | UN Temporary Commission on Korea |

| UNTSO | UN Truce Supervision Organization |

| UPR | Universal Periodic Review |

| US | United States (of America) |

| USI | United States of Indonesia |

| USDA | United States Department of Agriculture |

| USSR | Union of Soviet Socialist Republics |

| WEOG | Western European and Others Group |

| WFB | World Food Board |

| WFP | World Food Programme |

| WGIP | Working Group on Indigenous Populations |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WIPO | World Intellectual Property Organization |

| WMD | weapons of mass destruction |

| WNG | West New Guinea |

| WSSD | World Summit for Social Development/World Summit on Sustainable Development |

| WTO | World Trade Organization |

Introduction

The UN Security Council held its inaugural session on 17 January 1946 in Church House, Westminster. In the chair was the Australian representative, Norman Makin, then a Cabinet minister in the Chifley government and shortly to become Australian ambassador in Washington. His opening remarks began proceedings. He observed that 'the very great hopes' of 'the peoples of the world' centred upon the Security Council's work. Provided, he said, the principles of the Charter were adhered to by all its members, it would become 'a great power for good in the world, bringing that freedom from fear which is necessary before we can hope for progress and welfare in all lands'.1 Then, as now, Australia was ready to commit to the great objectives of the UN project.

The history of Australia's UN engagement

This book examines Australia's engagement with the United Nations, from its involvement in the UN's predecessor organisation, the League of Nations, to the present day. In Chapter 1, James Cotton shows how, as a founding member of the League of Nations, the early development of Australia's international personality owed a great deal to the requirements of the League. The debates and meetings at Geneva were a school in international issues for the young federation. Peace and security were initially at the forefront, but over time wider global concerns emerged, including health, economic development, gender and communications. Former prime minister Stanley Melbourne Bruce was Australia's most prominent representative at the League. He served on the League of Nations Council and was an active participant in a number of important negotiations; his greatest contribution, however, was to the social and economic work of the League. The Bruce Report of 1939 argued that the organisation's efforts to improve the human condition–through better nutrition, freer trade and technical and scientific cooperation–would in time erode many of the fundamental causes of international insecurities. This idea was too late for the League, but seminal for the development of the United Nations and its agencies.

At the 1945 UN Conference on International Organization at San Francisco–the conference which laid the foundations for the United Nations–another Australian was similarly prominent: Minister for External Affairs HV Evatt. In Chapter 2, Neville Meaney traces Evatt's many contributions to the debate on and drafting of the UN Charter, showing his tireless pursuit of a positive role within the United Nations for medium powers and smaller states. Later, as president of the General Assembly for the third session in 1948, he endeavoured to reconcile the claims of the major veto-wielding powers while seeking to find mechanisms that the United Nations could employ to avoid the confrontation of the looming Cold War. The 'Uniting for Peace' resolution of 1950 and more particularly the Assembly's first emergency special session of 1956, which established the first UN Emergency Force (to manage the Suez ceasefire), were only possible because of the earlier dogged insistence of the representatives of some of the middle powers, and especially of Evatt, that the United Nations should provide modalities for action on security that were open to all member nations. In a more general sense, the Assembly's willingness to take charge of issues such as climate change and even contribute to the management of development questions has been in accordance with Evatt's ambitions for what he described as the UN's democratic organs. As he stated in 1948:

[n]o power is so great that it can ignore the will of the peoples of the world expressed through the Assembly, and no power is so small that it cannot contribute to the making of world opinion through the Assembly.2

In Chapter 3, David Lee examines Australia's contributions as a member and non-member to the UN Security Council. The chapter focuses on Australia's four terms as a non-permanent member of that body (1945–46, 1956–57, 1973–74 and 1985–86) and on Australian diplomacy in several areas, notably East Timor, Cambodia and Iraq, when it was not a member. Despite being envisaged as the executive of the United Nations, the Council long laboured under the constraints imposed by the Cold War. Yet even in that atmosphere Australia made some important contributions. Presiding over the Security Council in October 1973, Australian Permanent Representative Sir Laurence McIntyre was instrumental in winning approval for Resolution 338 which called on all parties to effect a ceasefire in the escalating Arab–Israeli conflict. Australia then supported Resolution 340, establishing the UN Emergency Force in the Middle East under the direct control of the Council, which allowed the Soviet Union and the United States to disengage from their sponsorship of the antagonists.

Throughout its history the United Nations has remained an organisation under construction and renewal. In Chapter 11, Roderic Pitty examines the important role that Australia has played from 1945 to the present in seeking to improve the UN's performance and to ensure that the new challenges of global politics have been met. Aware that the very considerable powers of the Council could only be wielded effectively if its legitimacy was firmly grounded, Australian representatives at the United Nations have been strong proponents of the greatest practical degree of transparency in its deliberations. If the great powers were to delay or deny Council action by exercising their veto power, as was their right under the Charter, then the debate preceding such action should have the widest audience. The frustrations that were the consequence of Council inaction shifted the focus of attention and activity to the General Assembly, where the expansion of membership brought a diversity of views and demands.3 As offices and programs proliferated, Australia consistently adopted a firm line on the need to improve UN governance by laying down clear lines of authority, removing overlapping functions and responsibilities, and reforming poorly performing agencies. In 1994, seizing the post–Cold War moment, Minister for Foreign Affairs Gareth Evans advocated sweeping proposals for UN reform, including reform of the Secretariat and the Council–proposals that have continued to influence the reform agenda to this day.

While the role of peacekeeping was not envisaged in the Charter, not only did it prove one of the UN's earliest responsibilities but in many respects it has become the function most closely associated with the organisation. In Chapter 7, Moreen Dee looks at Australia's efforts to support UN peacekeeping from the very beginning, with its involvement in the Consular Commission, which was established by the Security Council in August 1947 to observe the ceasefire between Indonesian and Dutch forces, to the present day. Beginning with the contribution of military observers to the commission–arguably the first UN peacekeeping mission–Australian peacekeepers, with varying roles, have been part of some forty UN peacekeeping missions over the past sixty years. This contribution has included two longstanding commitments: to the UN Truce Supervision Organization in the Middle East since 1956 and to the UN Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus since it was established in 1964. In addition to major commitments to the UN Transitional Authority in Cambodia and the UN Transitional Administration in East Timor, Australia has taken the lead in several multinational peace missions in its own region, such as the International Force for East Timor and the Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon Islands. Australia's political, diplomatic and financial support for UN peacekeeping efforts has been constant. In the Special Committee on Peacekeeping Operations, it has played an active role in the development of innovative approaches to peacekeeping and peacebuilding, notably in advancing the idea of 'cooperative security'.

During the Cold War many of the goals espoused by the United Nations were obstructed as a result of great-power enmity. One objective that was widely accepted, however, was decolonisation, which became the focus of considerable attention within the organisation. In retrospect, as Matthew Jordan notes in Chapter 4, Australia's greatest contribution to this process took practical form in the preparation of Papua and New Guinea (the latter a UN-mandated territory) for self-rule and then independence, under consistent UN scrutiny and with the assistance of UN development agencies. In light of the many difficulties faced in parts of the decolonised world, the good relations enjoyed between Australia and Papua New Guinea, which continue to the present, are perhaps the best indicator of the soundness of that preparation. In the 1970s Australia strongly supported the completion of decolonisation, especially in Africa (including Zimbabwe), and was a critic, as a consequence, of the apartheid regime in South Africa.

Awareness of the complementary relationship between development, peace and security was a fundamental of Australian policy towards the United Nations from the earliest days. Even before the drafting of the Charter, Australian policymakers sought to ensure that the organisation included an Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) in order to make economic and social improvement a central part of the UN mission. In the early days of the United Nations, Australian policymakers had high hopes that ECOSOC would perform a major coordinating role in relation to the many specialised agencies in the UN family; however, these hopes were never realised, largely because of the limited authority of and funding available to the council. Australia was a founding member of the UN Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (established in 1943), and Australian personnel played an important part in immediate post-conflict relief efforts. The establishment of the Food and Agriculture Organization owed much to Australian thinking and advocacy; Australia was a founding member of the UN Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East, later the UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific; and Australian representatives in the Assembly supported the establishment of the Special UN Fund for Economic Development. With the reorganisation of the UN's development efforts, Australia became a member of the governing body of the UN Development Programme (UNDP) in 1966. Within the UN Conference on Trade and Development, Australia championed the argument that trade and development were inextricably linked; the parallel link between health and development informed Australia's scientific contributions to the World Health Organization, notably in the campaign to eradicate smallpox. Mindful of criticisms of agency duplication and confused administrative structures, the UNDP commissioned noted Australian international civil servant, Robert Jackson, to undertake a capacity study. Jackson's 1969 report, which is still cited by UN reformers today, proposed a refocusing of development efforts under a single authority, a strengthening of ECOSOC to superintend those efforts, and a unified program of development negotiated for each country. Other Australians have also made notable contributions to the UN's international economic and social activities. Under the leadership of Australian James Ingram from 1982, the World Food Programme provided a working example of effective aid and development delivery. Australia was an active participant in the process that led to the UN's adoption of the Millennium Development Goals, and Australia's provision of international aid is now benchmarked against these standards. Australia's level of official development assistance continues to expand to reach the target set by the Monterrey Consensus of 2002.

In a broader sense, the Bretton Woods institutions–the International Monetary Fund and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (the latter today part of the World Bank Group)–are collateral branches of the extended UN family. Australia was a beneficiary of World Bank loans in the later 1950s. In 1964, as a result of an invitation for an official mission to Papua and New Guinea, the Australian administration engaged the World Bank in development assistance in the territory. Peter Carroll examines Australia's engagement with the UN's specialised agencies, including the Bretton Woods institutions, in Chapter 5, and Chad Mitcham discusses Australia's contribution to the UN's broader development efforts in Chapter 6.

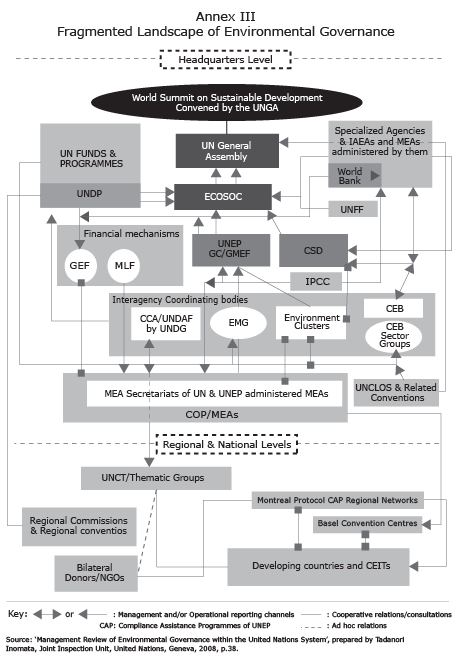

In Chapter 9, Lorraine Elliott examines Australia's engagement with the United Nations on environmental issues. In the earliest period of UN concern with environmental matters, Australia took a particular interest in the oceans, participating from 1958 in successive conferences on the law of the sea, and also becoming an early advocate for applying the precautionary principle to dealing with such issues as ocean pollution and conservation of marine species. Australia was a member of the UN Environment Programme's first Governing Council and has continued to serve on the council frequently; when the Commission on Sustainable Development was established in 1992, Australian representatives were also members of its first governing body. With the emergence of major global summits as vehicles for focusing attention on and addressing environmental questions, Australia has been a consistent participant. Australia was one of the sponsors of the General Assembly resolution that established the UN Conference on the Human Environment of 1972. At the UN Conference on the Environment and Development (the Rio Summit) in 1992, Australian proposals on the principles that should be the basis for dealing with the costs and remediation of environmental degradation were influential in the policy formulation finally adopted. At the subsequent World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg in 2002, Australia embraced the idea of 'action-oriented coalitions' bringing government and non-government actors together to tackle specific environmental issues. Though a late adherent to the Kyoto Protocol, Australia has continued to advocate a comprehensive grand bargain under UN auspices to limit global greenhouse gas emissions.

As Colin Milner observes in Chapter 10, Australia's contribution to the promotion of human rights and international law at the United Nations began with the drafting of the Charter: Article 56, which enjoins member states to observe the human rights specified in Article 55, termed the 'Australian pledge'. With Evatt in the chair, the Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The emerging UN human rights regime also had a strong impact on Australia's own policy, informing legislation on racial and gender discrimination, the status of women and Indigenous rights. The International Criminal Court enjoyed strong bipartisan support in the Australian parliament, and the 2010 launch by Canberra of a Human Rights Framework received strong approval in the UN's Universal Periodic Review of Australia's human rights record. When Australia's performance in observing human rights, including the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, has been found wanting, such findings have served as a reminder that UN scrutiny of domestic affairs against international standards is a necessary preventive against complacency.

Arms control and disarmament were important objectives for the League, and they were also among the major objectives of the founders of the United Nations, as Matthew Jordan shows in Chapter 8. From the beginning, Australia had high hopes for international control of atomic weapons and technology–the first meeting of the Atomic Energy Commission, established with that end, was chaired by Evatt. In the Cold War period, progress on disarmament was highly constrained, but when attempts were made to construct a treaty to control the spread of nuclear weapons, the effort won significant bureaucratic support in Canberra, and the Australian government signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in early 1973. Even before then Australian spokespersons had supported the idea of a nuclear test ban, voicing particularly strong opposition to atmospheric testing as a result of French tests in the Pacific from 1966 to 1996. In the 1980s Australia was active in the Conference on Disarmament as an advocate of a Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) and as a critic of further nuclear weapons development and deployment. The Australian focus on weapons of mass destruction broadened: in 1984 the hosting of what became the Australia Group led to supply-side measures to limit opportunities for the manufacture of chemical weapons. In 1992 Australia proposed a draft Chemical Weapons Convention to the Conference on Disarmament; the resulting convention was later accepted at the United Nations by consensus. In 1996 Australia's permanent representative to the United Nations in New York, Richard Butler, persuaded the General Assembly to accept a draft CTBT text. In the more sombre atmosphere following the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks in the United States, Australia supported UN Security Council Resolution 1540, which aimed to prevent materials or technologies for weapons of mass destruction passing into the hands of non-state groups. With the danger of further proliferation becoming more apparent in the new century, and in the context of US President Barack Obama's 2009 affirmation of the principle that nuclear weapons would eventually be abandoned, Australia sought a more innovative approach to this issue. The Australian government, which co-sponsored the International Commission on Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament, viewed the proposals of the commission's co-chairs, Gareth Evans and Yoriko Kawaguchi, as a blueprint for proceeding towards the goal of abandoning nuclear weapons altogether.

There is no chapter dedicated specifically to the history of Australian diplomacy in the UN General Assembly. The only organ of the United Nations in which all member nations have equal representation, the Assembly oversees the budget of the organisation, appoints non-permanent members to the Security Council, receives reports from other parts of the organisation and makes non-binding resolutions. Discussion of the General Assembly, however, features throughout the book. For example, Chapter 2 discusses Evatt's efforts to allow the Assembly a more prominent role in security matters, and Chapter 3 examines later occasions when it took on such a role, namely in the 'Uniting for Peace' resolution of 1950 and in the establishment of the first UN Emergency Force.

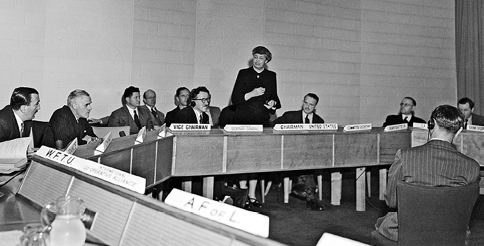

Just as the League had affirmed at its inception that all of its posts should be open to women, and then became an important international forum for advancing the status of women, the United Nations has always made the rights of women a central objective. Australia has consistently supported this objective, being one of the initial signatories to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, adopted by the Assembly in 1979. Australia has also supported UN Security Council resolutions that recognise the vital role of women in peacebuilding and that condemn sexual violence in areas of armed conflict.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) began as an affiliate of the League, and its tripartite organisation principles, requiring national delegations and negotiations to embrace labour, employers and state authorities, owed something to Australian precedent. With the demise of the League the ILO became part of the UN family, and Australia's engagement with its work to guarantee the standards and dignity of labour has been continuous. The International Institute of Intellectual Cooperation was also a League instrumentality; its functions were assumed by the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Unlike some Western countries, Australia (as is noted by Peter Carroll in Chapter 5) has been a continuous member of UNESCO since its inception, its National Commission for UNESCO making available expert advice on heritage, scientific, cultural and educational issues.

In addition to the states which are members of the United Nations, and the body of officials in New York, Geneva and elsewhere who constitute its working staff, there is a 'third United Nations'–of national and international groups that engage with the organisation in support of its aims or that seek to influence its agenda. In the era before 'non-government organisations' were commonly known as such, Australia was home to active branches of the League of Nations Union, an international movement centred in London that promoted international understanding, including by working in schools and the media. In 1945 the Australian chapters of the League of Nations Union became the United Nations Association of Australia, and from that time to the present the UN project has engaged many ordinary citizens. UN Women Australia, to take just one example, campaigns to ensure that the Australian government's agents in peace and security missions are aware of gender issues and pursue security outcomes that recognise and empower women.

While this book aims to present a thorough overview of Australia's engagement with the United Nations, there are many topics that could be explored at greater length. To take one example, Australia's support for the work of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees could well have been the subject of a chapter on its own. Moreover, many aspects of Australia's contributions to the development of international law, though important in themselves, have not been addressed in this book because they are outside the UN system. One example is Australia's long involvement with the Geneva Conventions, which were negotiated in the context of the role played by the International Committee of the Red Cross as guardian of international humanitarian law. To this extent, the book may provide an indication to scholars and researchers of further fruitful avenues for study and analysis in the rich story of Australia's contribution to global governance.

Conclusion

When the United Nations was conceived, the problems of war and reconstruction were pre-eminent. As this book shows, Australian contributions were at the forefront of programs designed to deal with both these pressing issues. While broader international objectives were also served by this effort, Australian policymakers focused principally on advancing the national interest. With the advent of the Cold War, Australian expectations of the organisation diminished. Writing in the 1950s, Norman Harper and David Sissons characterised the Australian view of the United Nations as principally 'a framework for co-operation with other like-minded powers'.4 With great-power rivalry impeding the resolution of many issues, development emerged as a major focus of UN activity. Australia has made a sustained contribution in this area, including through its support for attempts to simplify and rationalise the UN's increasingly complex development machinery. Again, the contribution to the national interest was a vital part of this commitment. As one Australian commentator of the early 1970s observed, development was 'a key to peace'.5

Since the 1970s, however, it has become ever clearer that the advancement of the national interest requires solutions to increasingly complex global problems for which responsibility is both international and diffuse. As Thomas Weiss and Ramesh Thakur have argued, in the absence of a global authority or government, 'governance' has become the key focus of the current era, and the idea of 'global governance' has emerged to describe attempts to deal with these challenges. Weiss and Thakur define this concept as:

the sum of laws, norms, policies, and institutions that define, constitute, and mediate transborder relations between states, citizens, intergovernmental and nongovernmental organizations and the market [coordinated] … to bring more predictability, stability and order to … such transnational problems as warfare, poverty, and environmental degradation that go beyond the capacity of a single state to solve and that are increasingly recognized as such.6

In this sense the United Nations has become the chief focus for global governance. Australian efforts through the United Nations–devoted to such objectives as non-proliferation and arms control, peacebuilding, improved food and agricultural production, scientific cooperation, and latterly the Responsibility to Protect and the pursuit of the Millennium Development Goals–may thus be seen as a major part of the nation's distinctive contribution to the unfinished tasks of global governance.

1. Australia in the League of Nations: Role, debates, presence

James Cotton

Australian membership of international society entered a new, and in many respects the beginning of its modern, phase when the nation became a founding member of the League of Nations in 1920. Transnational relations had always been an essential element in the definition of the Australian identity. Prior to 1914, when Australians looked beyond their borders it was exclusively to the British Empire–for security, for prosperity and, to a considerable degree, for authority. The advent of the League began the transformation of this outlook. The story of Australian involvement with the League is the subject of a fine, book-length study by WJ Hudson.7

This chapter sketches the circumstances under which Australia became an original member of the League and how this membership constituted an important element in the formation of Australia's international orientation as policymakers sought, first, to master the novel task of defending essential national objectives within an organisation of global character, and then to contribute to an emerging global discourse on international society. Australians had to face up to new international responsibilities, including being scrutinised for the policies pursued in New Guinea, held under a League mandate. Engagement with the League at Geneva also required the Australian government to take positions on issues of the day, including measures to promote peace and avoid war, that were beyond the familiar confines of imperial consultation. The chapter then considers the debates conducted within Australia on the character, claims and limitations of the League, and the responses of Australians to the disappointments and threats consequent on events in the 1930s.

The chapter concludes by examining briefly the role of some individual Australians who, as delegates, visitors, activists and bureaucrats, played their part in the debates and deliberations of Geneva. However modest this engagement was by contemporary standards, League membership was an important element not only in the schooling of Australian leaders in international responsibility, but also in the internationalising of Australian knowledge and opinion. The League was a school for international citizenship.

Australian membership of the League

The formation of the League of Nations was an integral part of the peacemaking process of 1919. The carriage of Australian policy towards the peace was in the hands of Prime Minister William Morris Hughes, whose abrasive style and confrontational tactics were not best suited to the complex negotiations that were conducted.8 Arriving in London in 1918, Hughes joined the Imperial War Cabinet where the shape of the future peace was under debate; he became a spokesman for those who supported a punitive policy towards Germany and was insistent upon Australia's title to the German New Guinea territories occupied in 1914. He was particularly dismissive of the 'Fourteen Points' that US President Woodrow Wilson had propounded in January as the basis for an end to the conflict. Wilson had not only proposed the formation of 'a general association of nations' (the future League of Nations) to preserve the peace but had made no mention of reparations from the defeated countries and had insisted that colonial territories should be dealt with solely from the point of view of the wellbeing of their inhabitants. Wilson believed that any other policies would sow the seeds of future wars. Hughes, who was of the opinion that warfare was part of the human condition, was enraged when he discovered that British Prime Minister Lloyd George had accepted Wilson's proposals without consulting Australia or the other dominions in the Imperial War Cabinet, a development which further encouraged a dogged insistence upon pursuing his view of the Australian national interest whatever the consequences. He was also unhappy with the time spent upon the plans of Robert Cecil and JC Smuts for a future world organisation which he was suspicious would undermine Australia's national sovereignty. With other dominion leaders, especially Canada's Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden, he advanced the argument–which was ultimately successful–that such an organisation must have a place for distinct representation of the dominions.

The negotiation of the peace, and also of the Covenant of the League of Nations, was accomplished in Paris in the first half of 1919. After some resistance the separate representation of the British dominions at the peace conference was agreed, but though the essential decisions were taken in the councils of the chief powers (the United States, the British Empire, France, Japan and Italy; later Japan was sidelined and Italy withdrew), Hughes took advantage of the fact that he was both the Australian representative and also part of the Empire delegation and was thus privy to the deliberations of the inner circle. The confrontations between Hughes and Wilson were the talk of Paris; when the negotiations concluded, in addition to Australia becoming a founding member of the new League, Hughes achieved two objectives which, by his lights, were essential for the promotion of Australia's security. First, Australia acquired the former German colony of New Guinea as a (Class 'C') mandate on very liberal terms, terms which had been incorporated in the Covenant of the League (in Article 22) directly as a result of the acuity of JG Latham, who was then serving as an adviser to the Australian delegation.9 Second, Japanese attempts to insert into the Covenant a reference to the principle of racial non-discrimination were defeated despite extensive support for the notion among the delegates.10 Hughes regarded this manoeuvre as the precursor to Japanese attempts to use international organisation to undermine the White Australia policy; the outcome was to rankle with Japan and serve as a continued irritant in bilateral relations thereafter. Hughes was especially sensitive to any suggestion that League obligations infringe domestic jurisdiction over such issues as immigration and tariffs. In this sense it may be claimed that Hughes ensured that international organisation helped to prolong empire,11 though it should be noted that the Japanese initiative was itself taken largely for domestic and imperial reasons.12

Beyond these specific objectives, Hughes had added his voice to those others within the British Empire delegation at Paris who were concerned that the early proposals for the Covenant would render the League less a consultative body than a supranational authority. Consequently he was critical of any suggestion that under its provisions members might become obliged to wage war or impose sanctions or conform to the judgements of an external judicial body (the Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ), envisaged under Article 14 of the League Covenant, was later established in 1922).13 The Australian delegation was remarkable not least for its inclusion, along with JG Latham, of FW Eggleston and Robert Garran (Latham becoming Australia's first minister to Japan, and Eggleston first minister to China),14 a trio of unusually talented individuals all of whom were to perform exceptional public service for the Commonwealth. In their different ways all became supporters of the League, including, upon their return to Australia, in the Sydney and Melbourne branches of the League of Nations Union (LNU). In Paris, however, though they were less sceptical of the potential for international organisation than Hughes, they were all in agreement that Australia's security was presently founded upon membership of the British Empire and thus also reliance upon the Royal Navy. Consequently, whatever hopes might be entertained for the future of the League, especially as a war preventive, in the meantime nothing should be done to weaken that security guarantee.

Australia's role in the League

The decisions of the League were taken by the Council, which was comprised of delegates from the four major powers–Great Britain, France, Italy and Japan (the United States did not take up membership)–that were joined by Germany in 1926, and in addition an elected group, initially of four countries (enlarged by stages to eleven countries). Australia served on the Council from 1934 to 1936, with former prime minister Stanley Melbourne Bruce acting as chair during the crucial negotiations following the reoccupation of the Rhineland by German forces, Germany having announced its departure from the League in 1933. The Council met five or more times a year and much diplomatic business was also transacted among its members, who often included foreign ministers, in more informal settings.

Australian attention was initially focused on the Assembly, which met annually and in which each nation had a single vote. Australian delegates usually caucused with other members of what was known as the 'British Empire delegation', where attention was often focused on harmonising views within the Empire–Commonwealth, but all countries took their place separately in the Assembly meetings. Nomination of delegates to the Assembly from Australia (each nation was entitled to three; alternates were also permitted) was initially a somewhat haphazard affair, but they included visiting federal ministers, the high commissioners in London, parliamentarians and academics; from 1922 they also included at least one woman. When SM Bruce became, from 1932, resident minister and then high commissioner in London, he became the leader of Australia's delegation, and also an increasingly respected figure of influence in the diplomacy of Geneva.15 His first appearance there, however, had been a matter of happenstance. In 1921, as a junior backbench member of parliament touring the continent, he responded to an urgent summons from the government to attend the Assembly. As a war veteran, he spoke with some passion, applauding the League's mission 'to substitute the law of justice for the hideous arbitrament of war'.16 He warned, however, against the organisation taking on too many tasks as he felt this would be likely to deflect energies from this new international project which was of overriding importance.

The issue of disarmament, being one of the chief rationales for the establishment of the organisation, was indeed to occupy much of the League's time. However, great-power reluctance to accept the full implications of this objective delayed the convening of the long-envisaged full intergovernmental Conference for the Reduction and Limitation of Armaments until 1932, by which time the growth of extremist movements in Europe had ensured its futility. One of the obstacles in the way of serious disarmament was the objection that the collective security arrangements envisaged by the League Covenant were not sufficiently comprehensive, and consequently that states were bound to cling to the means of self-help. An attempt to tighten the requirements was initiated at the 1924 Assembly when British Prime Minister (and concurrently Foreign Secretary) James Ramsay MacDonald proposed a system of compulsory arbitration.17

As it stood, the Covenant (Article 15) required states to submit a dispute (not otherwise subject to arbitration) to the Council and to abide by its decision. However, if the Council failed to agree regarding the remedy for such a dispute, once three months had elapsed the state in question could still make war (under Article 12) without suffering the automatic sanctions prescribed in the Covenant (under Article 16). To deal with this 'gap' in the League system of security, a protocol was formulated by members of the Assembly in committee. It recommended, first, that all states unanimously recognise the remit of the PCIJ to determine on disputes of a judicial character (by adhering to the 'Optional Clause' of the court's defining statute). Second, disputes not brought before the court or otherwise arbitrated would necessarily become the business of the Council which, if it could not decide, would provide for arbitrators whose decision was binding on the disputants. States that did not adhere to these rules and which engaged in warfare would be deemed aggressors, and would be subject to the collective action of the other member states. War would be forsworn by all states other than to counter aggression at the behest of the Council or the Assembly. To provide an atmosphere conducive to these undertakings, a full disarmament conference was to be convened in the following year. 'Arbitration, security, disarmament' was the trilogy of the time. In a development that would have important consequences for Australia, the delegates of Japan proposed a modification to the protocol which appeared to weaken the Covenant's recognition (under Article 15, paragraph 8) that matters of domestic sovereignty were not the province of the Council. In their argument, the Japanese delegates referred both to the difficulties their nationals might face in China and also to the restrictive immigration practices of some Pacific countries.18 Although the original amendment suggested by Japan was considerably weakened, Article 5 of the new protocol seemed to require that states accept the judgement of the PCIJ on whether or not any question pertained to domestic sovereignty; it also explicitly allowed that even domestic matters could be deemed by the Council or Assembly as a threat to the peace and thus (under the Covenant, Article 11) a concern for the League.

MacDonald's tenure of office was brief, and there was a good deal of opposition to the protocol within the successor Conservative government, especially to the possibility, as it was seen, that Britain might be required to put the Royal Navy at the disposal of the League, or that the new arrangements would even risk conflict with the United States. But even before this opposition became clear, the protocol had raised apprehension in Australia.

The protocol had generated a good deal of interest (and a degree of fearmongering) in the Australian press. In a development without precedent in Australian diplomacy, Sir Littleton Groom (Attorney-General and Minister for Trade and Customs), the leader of Australia's delegation to the League, though instructed by Prime Minister Bruce to abstain when the protocol was discussed at the plenary meeting of the Assembly, voted in its favour. All other Empire delegates voted likewise, Groom probably being swayed by considerations of Empire solidarity.19 The protocol's provisions were outlined by Bruce in parliament only a day after it was adopted.20 He declared that Article 5 raised issues 'in which Australia is interested and in regard to which we must exercise the utmost vigilance'.21 In general, he took the position that the protocol represented 'progress' towards the noble objectives for the attainment of which the League had been established, and that Australia's sole concern related to any changes which might infringe upon domestic sovereignty. He particularly noted the contribution of the Japanese delegates and the context of their intervention, which was the failure of the League to adopt the principle of racial equality. In response to an interjection from Hughes, now on the back bench, that 'a fundamental change' had been made regarding the League's powers of scrutiny of domestic matters, Bruce was insistent that, so far, there had been no such alteration. But he did add that 'Australia cannot allow action regarding a question of domestic jurisdiction to be dictated to her by the League of Nations or by any other outside authority'.22 Hughes was not slow to claim in the press that Article 5 'gravely imperilled our White Australia'.23

In the event, Australia's reasons for rejection of the protocol (for which parliamentary assent would have been required) were conveyed to a government in London which had already made the same decision. The reasons Bruce offered included many of the objections voiced by the British, based on the fundamental assumption that the League was more likely to be effective as a vehicle for moral suasion than a legal organisation governed by inflexible rules. In the present state of world opinion, and especially given the absence from membership of important powers, the protocol represented, he wrote, 'a dangerous attempt to accelerate [the] growth' of a still imperfect regime which had yet to develop sufficiently robust foundations of 'mutual confidence'.24 But the issue that most engaged local opinion had been the putative threat to the White Australia policy. If Australians were learning to become citizens of the world, they were as yet little inclined to share their dwelling with others.

However, the momentum created by the protocol was not completely lost. At Locarno, five treaties were concluded, the most important of which guaranteed Germany's frontiers with France and Belgium, any violation of which would be brought to the Council and regarding which Britain and Italy agreed to act to punish the aggressor. Though the Locarno treaties were outside the League system, and their provisions (to quote a contemporary Australian scholar) 'constituted only a strictly limited settlement in a specially troublesome quarter of Europe',25 with France's security thus underwritten they did open the door to the entry of Germany into the League and to membership of the Council. Significantly, though the Australian government was kept informed of the negotiations, the dominions were not parties to the final arrangements, though they were given the option of becoming associated with the treaties. At the Imperial Conference of 1926, they decided not to do so, in the light of Canadian and South African reservations.

Despite the failure of the protocol, the desire of some League members to create a law-bound international sphere remained. The General Act for the Pacific Settlement of Disputes, prescribing specific measures of arbitration and conciliation between states in dispute, was debated in the 1928 League Assembly, and accepted by the Empire–Commonwealth members, including Australia, in 1930. In addition, a movement was initiated to expand the competence of the PCIJ, in particular by encouraging member states to adopt an optional clause which provided for the obligatory acceptance of the court's decisions on a wide variety of matters of fact and law. Although Australia had signed the protocol drawn up to signify acceptance of the role of the new PCIJ in 1921, it had not adopted the optional clause. At the 1926 Imperial Conference the Empire's view of the clause was discussed; the Australian delegation was led by Prime Minister Bruce, its members including Professor W Harrison Moore of the University of Melbourne who served as legal adviser. Bruce was doubtful of accepting the unqualified competence of the court, not least on the grounds that it was still unclear what law would apply. Further discussion of the matter in the League Assembly, the restatement of the preference of Canada to adopt the optional clause, and the election of a Labour government in the United Kingdom that was more sympathetic towards the Canadian view then prompted further review of the issue, and a conference was hastily convened in August 1929 in London to attempt to formulate a common Empire position in advance of the forthcoming meeting of the League Assembly. CWC Marr, in charge of the Australian delegation at the League and a minister without portfolio, was charged with the task, with Harrison Moore dispatched as his expert colleague, of representing Australia. Marr's brief was to delay any decision until further consultation, as well as to obstruct any unilateral action by other Empire members.26 The matter was first debated in an enlarged British Cabinet Committee in London, chaired by the Prime Minister, Ramsay MacDonald.

The Australian government remained convinced that accession to the clause was possible only with very specific reservations. According to a Department of External Affairs memorandum, the grounds for the lack of Empire unity on the optional clause related to the following issues:

(a) disputes in time of war, (b) the desirability and necessity of excluding certain possible disputes touching questions affecting domestic policy, (c) giving effect to decisions of the Court on matters of vital interest where such decisions would necessitate the passing of legislation, (d) the uncertainty of the rules of procedure followed by the Court, [and] (e) the uncertainty of the law to be applied by the Court.27

The document then referred to the Canadian position which was that the time had come for the Empire to accept the clause, noting that this was not the Australian view and that more time and discussion was needed. Although the Australian desire to delay further action was unsuccessful, Harrison Moore played an important role, as Hudson points out, in advising the government that it would be prudent to insist upon stating a reservation regarding matters of domestic jurisdiction. In the event, Britain and the other dominions accepted the optional clause, though reserving some categories of disputes, including those between British states and those regarding domestic jurisdiction.28 As to the latter, Harrison Moore undoubtedly had in mind questions of race and immigration, issues of distinct relevance to Australia. Once more, the desire to preserve matters of 'domestic jurisdiction', which meant the White Australia policy and also tariffs, from League scrutiny indicated that there were clear limits to Australian internationalism.

The League's increasingly complex web of measures and agreements were tested and found wanting in the following decade. Australia's contribution at the League to the crises of the 1930s was largely associated with the person of Bruce who not only led every national delegation to Geneva between 1932 and 1939 but also became an increasingly influential figure in League deliberations including within the Council. Bruce remained based in London though he was a frequent traveller to Geneva; unlike Canada, which had appointed an 'Advisory Officer' to be resident at the League from 1925 (with Walter A Riddell occupying the post until 1937),29 Australia maintained no permanent mission.

The global economic crisis which began in 1929 with the Wall Street crash unleashed forces that the international order of the 1920s, to which the League had been a major contributor, could not accommodate. In retrospect, the occupation in 1931 of northeast China by Japanese military forces, after the staging of a 'terrorist incident' on the Japanese-controlled railway at Mukden (Shenyang), marked the beginning of the decline of that international order. Though that region was under the effectively independent control of a warlord, China at the League brought the issue before the Council under the terms of Article 11 of the Covenant. Even though the United States, regarding the issue of major strategic import, had sent a delegate to attend, and the Council's members were unsympathetic to Japanese claims that their special interests in Manchuria were in jeopardy, they could not take action since Japan, as a member, in effect held a veto given that the League's procedures in relation to Article 11 at the time required unanimity. The best the Council could manage was an agreement to dispatch a Commission of Inquiry under Lord Lytton.

While Lytton and his fellow commissioners were making their leisurely way to the Far East (travelling first to Tokyo), Japan consolidated its control of Manchuria, set up an ostensibly independent administration in the region, and then extended military action to Shanghai, bombing civilian districts with significant loss of life. The Council again considered events in the Far East, the Chinese delegate invoking Article 15 of the Covenant and addressing his appeal to the whole Assembly. After much delay, and with Lytton's recommendations finally to hand, the Assembly voted in February 1933 to condemn Japan, whose delegates subsequently walked out of the League.

Bruce, in his first participation in League affairs at Geneva since 1922, spoke at the Assembly meeting in December 1932 when some smaller powers were calling for harsh censure of Japan while the British were attempting to hold the door open for some form of mediation. Though Bruce was well aware, as he said, that 'the League was in danger', he was concerned with seeking a solution that would be consistent with the fact that 'the authority of the League is based upon moral and not upon physical force'. Taking his cue from the British, he interpreted Lytton as showing that 'the rights and wrongs in this great question are neither on the one side nor on the other' and therefore deprecated any recourse to condemnation.30 As tensions mounted, the Australian government instructed him to avoid any involvement in actions that might result in a commitment to war against Japan.31 The Manchuria issue indeed marked a turning point for the League, but the larger context for the League's inaction is sometimes neglected. The major European powers enjoyed considerable extraterritorial rights in China proper, in regions, unlike Manchuria, which were under actual central government control; unequivocal condemnation of Japan would have been hypocritical. More important was the fact, which Bruce recognised clearly, that a League without Japanese membership, and especially without Japan–the most important Asian power–on the Council, would not command the power to bring its decisions to effect. Only in September 1938, after the Sino-Japanese war proper had been raging for a year, did China finally convince the Council to impose sanctions on Japan (under Article 16 of the Covenant); concrete actions, however, were left to the individual states, and Australia along with all the other powers ignored this directive.

In the midst of the Manchuria crisis, the first session of the long-delayed Conference for the Reduction and Limitation of Armaments of the League convened. In one respect the conference was without precedent, embracing sixty-four countries (including the United States and the Soviet Union); in another, as it began while Japanese troops were fighting near Shanghai, it represented a movement which had had some influence in the 1920s but the impetus of which was now largely spent. Until this point the Australian government had shown little interest in the League's work on disarmament. In any event, in the early 1930s the country had been all but disarmed by the budgetary economies forced upon the government by the Niemeyer mission and its London creditors; the rationale for Canberra's decision to attend therefore lay in the need to reinforce Empire solidarity. The newly elected government of Prime Minister Joseph Lyons appointed JG Latham (Minister for External Affairs and Attorney-General) to the Australian delegation, with the support of Sir Granville Ryrie, High Commissioner in London. Latham actually spent little time at Geneva, being absorbed by imperial business in London; Ryrie's extempore address, however, which drew on his Gallipoli experiences to condemn the unreason of war, made a strong impression.32 The substantive Australian contribution to the conference was slight, and when Germany–unable to secure parity in armaments–left the conference, the inability of the League machinery to address one of the central tasks specified in the Covenant became clear.33 An economic counterpart to the disarmament meeting was the World Monetary and Economic Conference, convened in London in 1933, at which Australia was represented by Bruce. Its outcome was no more positive, as there was a breakdown in attempts by the major economic powers to stabilise currencies.

In Australia, however, it was the Ethiopia issue that was perceived as the League's moment of truth.34 At Wal Wal, in border territory which lay in Ethiopia but was occupied by Italy, a military clash in December 1934–and subsequent Italian claims for compensation and apology–led to Ethiopia bringing the dispute to the Council. Despite the fact that Ethiopia was a member of the League, and that Italy's aggressive intentions were quite apparent, the Italian tactics of prevarication and dissimulation were abetted by most members of the Council, with Britain and France taking the lead in seeking a settlement that would be palatable to Mussolini. When the Council finally did consider the issue directly, as in the case of Manchuria it initially refused to act under Article 11 (which required unanimity).