Australia's Uranium Production and Exports

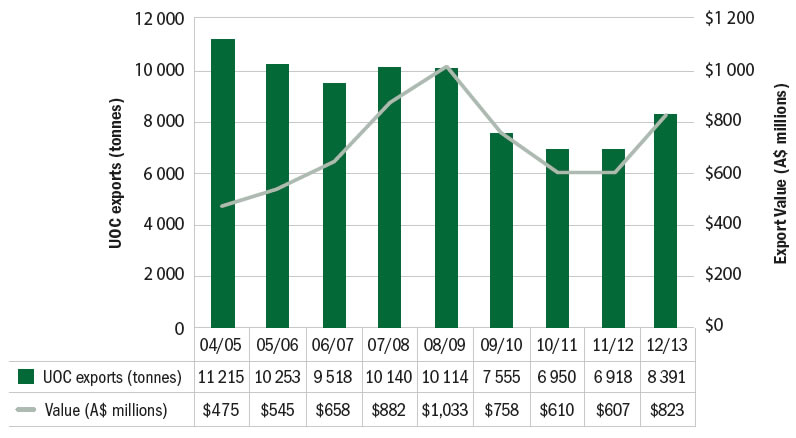

Statistics related to Australia's exports of uranium ore concentrates (UOC) are listed in Table 1 below.

Australia's Reasonably Assured Resources (RAR) of uranium recoverable at costs of less than US$130 per kilogram uranium were estimated to be 1,196,000 tonnes uranium as at December 2011, which represents 34 per cent of world resources in this category. This is based on estimates for Australia by Geoscience Australia in Australia's Identified Mineral Resources 2012 and for other countries as reported by the OECD Nuclear Energy Agency in 'Uranium 2011: Resources, Production and Demand'. In 2012, the Olympic Dam and Ranger mines were, respectively, the world's second largest (6 per cent of world uranium production) and third largest (5 per cent of world uranium production) uranium producers.10 Overall, in 2012 Australia was the third largest uranium producer after Kazakhstan and Canada.

Table 1: UOC export and nuclear electricity statistics

Item |

Data |

|---|---|

UOC Exports |

|

Total Australian UOC exports 2012–13 |

8 391 tonnes |

Value Australian UOC exports |

A$823 million |

Australian exports as % world uranium requirements11 |

~10.7% |

No. of reactors (GWe) these exports could power12 |

~40 |

Power generated by these exports |

~253 TWh |

Expressed as percentage of total Australian electricity production13 |

~99.6% |

Worldwide, uranium mining currently provides about 85 per cent of global industry requirements, with the balance coming from down-blending of excess weapons material, stockpiles and reprocessing. In 2012 world uranium consumption decreased due to lower consumption in Japan and Germany associated with the closure of nuclear capacity following the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear accident in March 2011. It is anticipated that world uranium consumption will increase in 2013 due to commissioning of new nuclear generating capacity in China, India, the Russian Federation and Taiwan. Over the longer term uranium spot prices are expected to be strong due to the forecast increase in nuclear power worldwide, and the completion of the 20 year US–Russia Megatons to Megawatts program, due to expire in 2013. New mines will be necessary to meet current, as well as future increases in demand.

Figure 2: Quantity and value of Australian UOC exports

Australia's nuclear safeguards policy

The Australian Government's uranium policy limits the export of Australian uranium to countries that are a party to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT),14 have an Additional Protocol in force and are within Australia's network of bilateral nuclear cooperation agreements. These nuclear cooperation agreements are designed to ensure that IAEA safeguards and appropriate nuclear security are applied, as well as a number of supplementary conditions. Nuclear material subject to the provisions of an Australian nuclear cooperation agreement is known as Australian Obligated Nuclear Material (AONM). The obligations of Australia's agreements apply to uranium as it moves through the different stages of the nuclear fuel cycle, and to nuclear material generated through the use of that uranium.

All Australia's nuclear cooperation agreements contain treaty-level assurances that AONM will be used exclusively for peaceful purposes and will be covered by safeguards arrangements under each country's safeguards agreement with the IAEA.

In the case of non-nuclear-weapon states, it is a minimum requirement that IAEA safeguards apply to all existing and future nuclear material and activities in that country. In the case of nuclear-weapon states, AONM must be covered by safeguards arrangements under that country's safeguards agreement with the IAEA, and is limited to use for civil (i.e. non-military) purposes.

The principal conditions for the use of AONM set out in Australia's safeguards agreements are:

- AONM will be used only for peaceful purposes and will not be diverted to military or explosive purposes (here military purpose includes: nuclear weapons; any nuclear explosive device; military nuclear reactors; military propulsion; depleted uranium munitions, and tritium production for nuclear weapons)

- IAEA safeguards will apply

- Australia's prior consent must be sought for transfers to third parties, enrichment to 20 per cent or more in the isotope 235U and reprocessing15

- fallback safeguards or contingency arrangements will apply if for any reason NPT or IAEA safeguards cease to apply in the country concerned

- internationally agreed standards of physical security will be applied to nuclear material in the country concerned

- detailed administrative arrangements are applied between ASNO and its counterpart organisation, setting out the procedures to apply in accounting for AONM

- regular consultations on the operation of the agreement are undertaken

- provision is made for the removal of AONM in the event of a breach of the agreement.

Australia currently has 22 nuclear safeguards agreements in force, covering 39 countries plus Taiwan (see Appendix B).16

Accounting for Australian uranium

Australia's bilateral partners holding AONM are required to maintain detailed records of transactions involving AONM. In addition, counterpart organisations in bilateral partner countries are required to submit regular reports, consent requests, transfer and receipt documentation to ASNO. ASNO accounts for AONM on the basis of information and knowledge including:

- reports from each bilateral partner

- shipping and transfer documentation

- calculations of process losses and nuclear consumption, and nuclear production

- knowledge of the fuel cycle in each country

- regular reconciliation and bilateral visits to counterparts

- regular liaison with counterpart organisations and with industry

- IAEA safeguards activities and IAEA conclusions on each country.

Australia's uranium transhipment security policy

For countries with which Australia does not have a bilateral safeguards agreement in force, but through which Australian uranium ore concentrates (UOC) are transhipped, there must be arrangements in place with such states to ensure the security of UOC during transhipment. If the state is:

- a party to the Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material (CPPNM)

- has adopted the IAEA's Additional Protocol on strengthened safeguards

- and acts in accordance with these agreements;

- then arrangements on appropriate security can be set out in an instrument with less than treaty status17. Any such arrangement of this kind would be subject to risk assessment of port security.

- For states that do not meet the above requirements, treaty-level arrangements on appropriate security may instead be required.

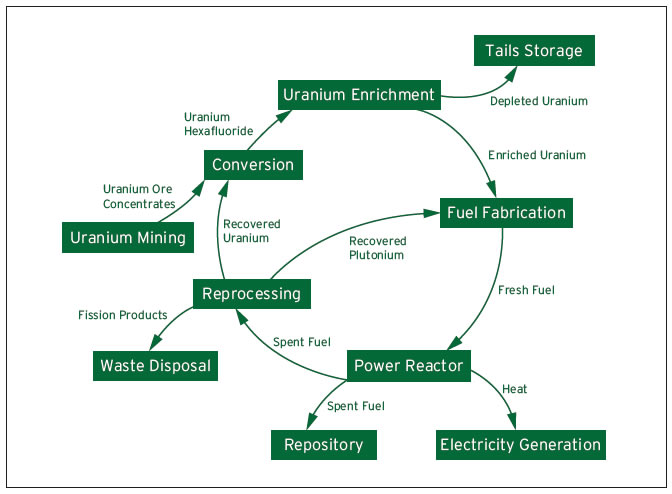

Figure 3: Civil Nuclear Fuel Cycle

A characteristic of the nuclear fuel cycle is the international interdependence of facility operators and power utilities. It is unusual for a country to be entirely self-contained in the processing of uranium for civil use. Even in the nuclear-weapon states, power utilities will often go to other countries seeking the most favourable terms for uranium processing and enrichment. It would not be unusual, for example, for a Japanese utility buying Australian uranium to have the uranium converted to uranium hexafluoride in Canada, enriched in France, fabricated into fuel in Japan and reprocessed in the United Kingdom.

The international flow of nuclear material means that nuclear materials are routinely mixed during processes such as conversion and enrichment and as such cannot be separated by origin thereafter. Therefore, tracking of individual uranium atoms is impossible. Since nuclear material is fungible – that is, any given atom is the same as any other – a uranium exporter is able to ensure its exports do not contribute to military applications by applying safeguards obligations to the overall quantity of material it exports. This practice of tracking quantities rather than atoms has led to the establishment of universal conventions for the industry, known as the principles of equivalence and proportionality. The equivalence principle provides that where AONM loses its separate identity because of process characteristics (e.g. mixing), an equivalent quantity of that material is designated as AONM. These equivalent quantities may be derived by calculation, measurement or from operating plant parameters. The equivalence principle does not permit substitution by a lower quality material. The proportionality principle provides that where AONM is mixed with other nuclear material and is then processed or irradiated, a corresponding proportion of the resulting material will be regarded as AONM.

10 Australian production compared with data on global uranium producers from the World Nuclear Association's World Uranium Mining (July 2013) – http://www.world-nuclear.org/info/Nuclear-Fuel-Cycle/Mining-of-Uranium/World-Uranium-Mining-Production/.

11 Based on 2013 world requirements of 66,512 tonnes uranium from the World Nuclear Association's World Nuclear Power Reactors & Uranium Requirements (1 July 2013) – http://www.world-nuclear.org/info/Facts-and-Figures/World-Nuclear-Power-Reactors-and-Uranium-Requirements/.

12 Based on a comparison of GWe of nuclear electricity capacity and uranium required, for countries eligible to use AONM from the World Nuclear Association's World Nuclear Power Reactors & Uranium Requirements (1 July 2013) – http://www.world-nuclear.org/info/Facts-and-Figures/World-Nuclear-Power-Reactors-and-Uranium-Requirements/.

13 Based on Australia's electricity generation in 2011–12 of 254 TWh from the Australian Government Bureau of Resources and Energy Economics' 2013 Australian Energy Update (July 2013) – http://www.bree.gov.au/publications/aes.html.

14 On 17 October 2012, the Australian Government announced that it would exempt India from its policy allowing supply of Australian uranium only to those States which are Parties to the NPT subject to the conclusion of a bilateral civil nuclear cooperation agreement that met Australia's safeguards and other requirements.

15 Australia has given reprocessing consent on a programmatic basis to EURATOM and Japan. Separated Australian-obligated plutonium is intended for blending with uranium into mixed oxide fuel (MOX) for further use for nuclear power generation.

16 Twenty-seven of the countries making up this total are European Union member states.

17 See page 26 of ASNO's 2008-09 Annual Report for more details on the establishment of this policy.